Last week New York Times video journalist Johnny Harris asked a simple question.

“What do Democrats actually do when they have all the power?”

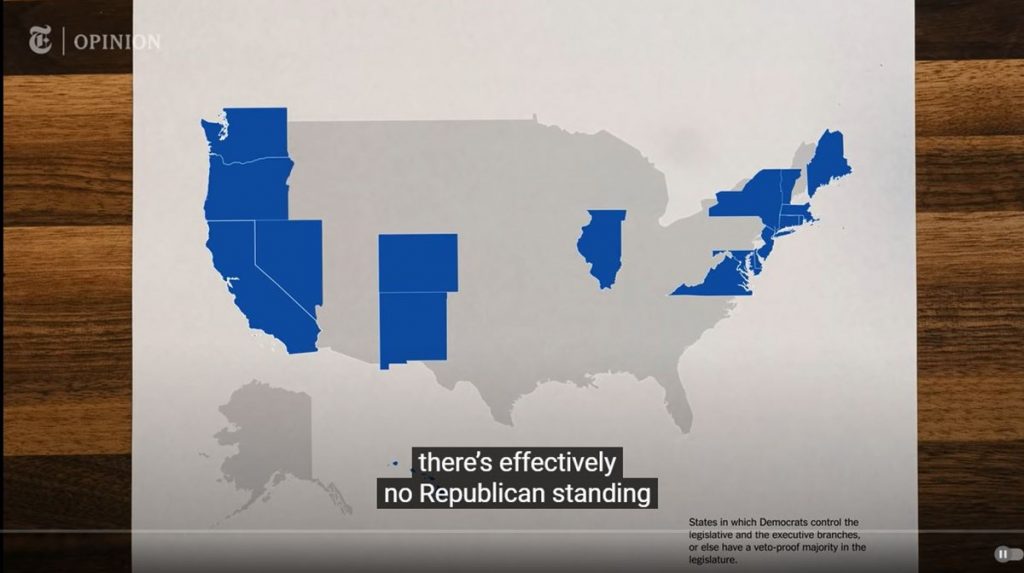

It turns out that 18 states in the US are effectively run by Democrats, who control both the executive and legislative branches. As Harris notes, Democratic leaders tend to blame Republicans for foiling their progressive plans, but that’s hardly the case in these 18 states where Republicans stand well away from the levers of power.

To answer his question—what do Democrats do when they have power?—Harris teamed up with Binyamin Appelbaum, the lead writer on business and economics on the Times editorial board and author of The Economists’ Hour.

What they found may surprise you.

‘Housing Is a Human Right’

First, Harris and Applebaum drilled into the 2020 Democratic Party Platform to see which values were most important to Democrats. They then focused on a particular state: California, the “quintessential liberal state” where Democrats rule with ironclad majorities and control the government in most major cities. Finally, the journalists decided to look at one specific policy: housing.

As Harris notes, housing policy is not exactly sexy stuff. But Applebaum stresses just how important housing is in battling inequality.

“Looking at California, you have to look at housing,” Applebaum says. “You cannot say you are against income inequality in America unless you are willing to have affordable housing built in your neighborhood….The neighborhood where you are born has a huge influence on the rest of your life.”

Moreover, Harris points out that Democrats overwhelmingly agree on its vital importance, noting that the word housing is mentioned more than 100 times in the Democrats’ platform. Indeed, Democrats are shown repeating a common mantra in the Times video.

“Housing is a human right.”

“Housing is a human right.”

“Housing is a human right.”

So How Does California Score on Housing?

Democrats may say housing is a human right, but Applebaum notes their actions say something else, at least in California.

“You know those signs where you drive into a state and it says ‘Welcome to California’?” asks Applebaum. “You might as well replace them with signs that say KEEP OUT. Because in California the cost of housing is so high that for many people it’s simply unaffordable.”

As the Los Angeles Times noted in 2019, California has “an overregulation problem,” which is why nine of the 15 priciest metro areas in the US are in California and the median price of a house in San Diego is $830,000. In some cases, people have had to wait 20 years to build a pair of single family homes. (Applebaum, it’s worth noting, appears to misdiagnose the problem. He complains that “the state has simply for the most part stopped building housing.” Perhaps Applebaum simply misspoke, but it’s worth noting the state doesn’t need to build a single unit of housing; it simply needs to step back and allow the market to function.)

Regulations, however, aren’t the full story. As Harris notes, Californians themselves have fought tooth and nail to keep higher-density affordable housing out of their neighborhoods. Palo Alto is cited as an example, where voters in 2013 overturned a unanimous city council vote to rezone a 2.46-acre site to enable a housing development with 60 units for low-income seniors and 12 single-family homes.

“I think people aren’t living their values,” Applebaum says. “There’s an aspect of sort of greed here.”

Housing isn’t the only area the Times journalists find where progressives fail to “live their values.” Washington state having the most regressive tax rate in the US is cited as another example, as are the “gerrymandered” school districts in states like Illinois and Connecticut that consign low-income families to the least-funded schools because of their zip code.

The journalists are left with a gloomy conclusion.

“For some of these foundational Democratic values of housing equality, progressive taxation, and education equality, Democrats don’t actually embody their values very well,” Harris says.

Applebaum is even more blunt.

“Blue states are the problem,” the economics writer says. “Blue states are where the housing crisis is located. Blue states are where the disparities in education funding are the most dramatic. Blue states are the places where tens of thousands of homeless people are living on the streets. Blue states are the places where economic inequality is increasing most quickly in this country. This is not a problem of not doing well enough; it is a situation where blue states are the problem.”

Harris says affluent liberals “tend to be really good at showing up at the marches” and talking about their concerns over inequality. But when rubber meets the road, they tend to make decisions based on a different calculus: what benefits them personally.

The Butcher, the Brewer, and the Baker

For some, the findings and claims of the Times journalists could be jarring. But they are likely no surprise to FEE readers.

One of the pillars of public choice theory—a school of economics pioneered by Nobel Prize-winning economist James Buchanan—is that people make decisions based primarily on self-interest. (People act out of concern for others, too, but these interests tend to be secondary to self-interest.) Buchanan’s theory rests on the idea that all groups of people tend to reach decisions in this manner, including people acting in the political marketplace such as voters, politicians, and bureaucrats.

Many believe that self interest is part of the human condition, something as natural as hunger, love, and procreation. Harnessing the instinct of self-interest in a healthy way—through free exchange—has long been considered a cornerstone of capitalism and a key to a prosperous society.

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest,” Adam Smith famously observed in The Wealth of Nations. “We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our necessities but of their advantages.”

For many progressives, however, self-interest has become a kind of heresy. The idea that individuals should be motivated by such things as profit and self-interest is anathema; these are values to be found in Ayn Rand novels, not practiced in 21st century America.

But as Applebaum notes, progressives are in fact making decisions based on self-interest—he uses the word “greed”—not altruism. This should come as little surprise, and it would be perfectly fine if progressives were acting on self-interest in a market economy; but they are not. They are using the law in perverse ways to their own benefit—all while maintaining the belief that they’re acting out of altruism.

The Times article makes it clear that voters and politicians in progressive states still arrive at decisions like everyone else: on self-interest. The results are just far worse when those decisions are made in the political space, not the marketplace.

Jon Miltimore

Jonathan Miltimore is the Managing Editor of FEE.org. His writing/reporting has been the subject of articles in TIME magazine, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, Forbes, Fox News, and the Star Tribune.

Bylines: Newsweek, The Washington Times, MSN.com, The Washington Examiner, The Daily Caller, The Federalist, the Epoch Times.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.