American college graduates are suffering financially under the weight of $1.5 trillion of student loan debt. The bulk of that debt stems from worrisome federal student loan practices and ballooning state tuition costs. Approximately 75 percent of college students attend a state university or college with tuition rates set by legislatures or state institutions. Over 85 percent of student loans are generated under the federal student loan program. In the past three decades, tuition at state colleges has increased by 313 percent.

Oddly, some seem to blame “capitalism” for the student loan predicament. Ray Dalio, billionaire investor, cited massive student debt loads in a recent article that made the case for reforming capitalism. Presidential Candidate John Hickenlooper penned an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal boldly proclaiming he is running for president to save capitalism. The very first point in his argument is that (public) high school education doesn’t provide adequate training for the modern economy. Anecdotally, we have heard the federal student loan predicament conflated with capitalism.

The Hardship Is Real

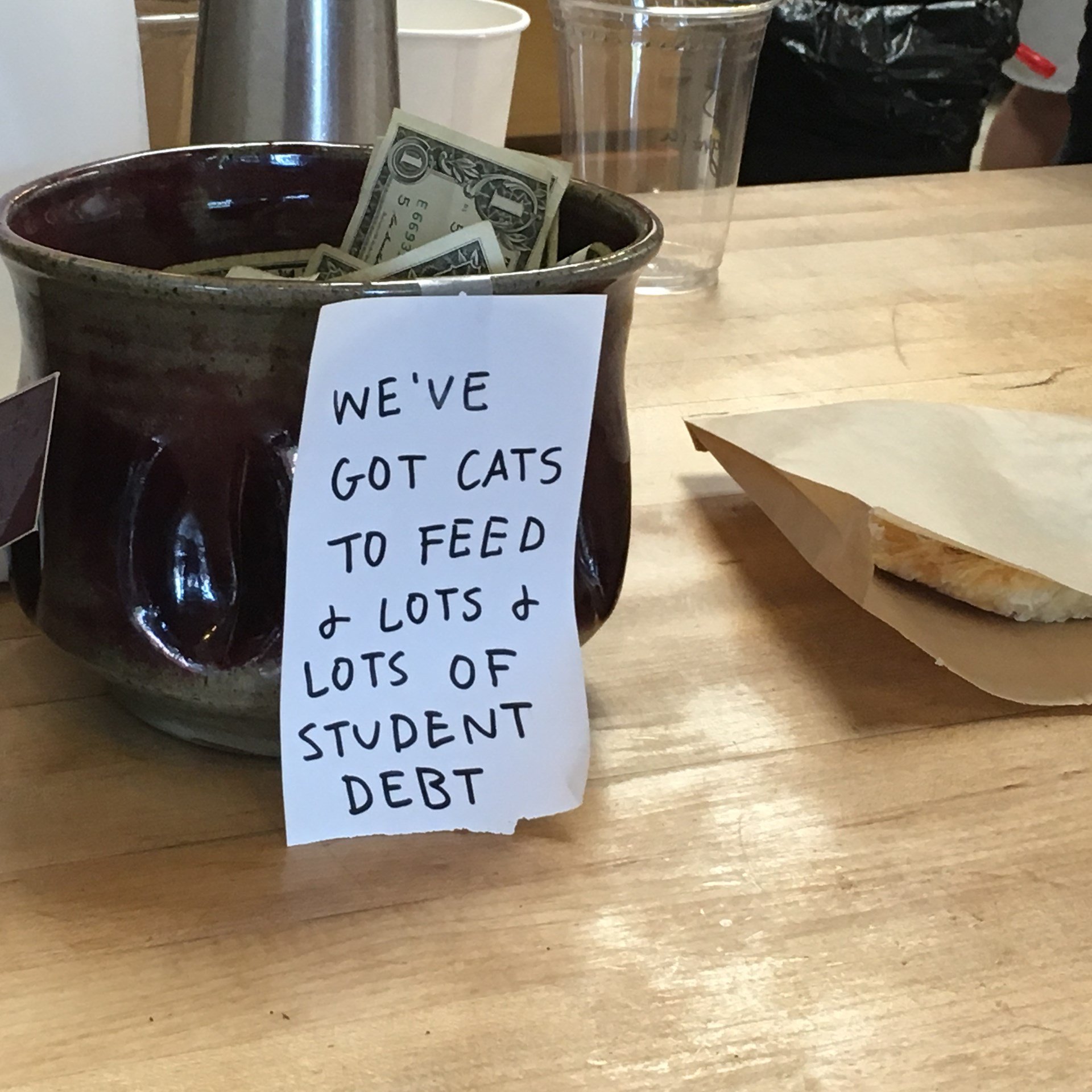

The pain of student debt is real. Sadly, there are many adults burdened by thousands of dollars in loan debt. Khalilah Beecham-Watkins, a first-generation college student and young mom, is one of many who feels as if they’re a prisoner to student loan debt. Khalilah has been working to pay down her $80,000 debt while helping her husband tackle his own loan obligations. In an interview last year, she said, “I feel like I’m drowning.”

As is well-reported, many young adults feel like Khalilah. In the United States, the average student loan debt is more than $37,000. As unsettling as that figure is, some graduates face even higher debt loads. About five percent of degree earners have student loan debt totaling $100,000 or more. Stories like Khalilah’s need to be told so that students don’t flippantly take on crushing debt without recognizing the gravity of such a decision.

This significant debt load is exacerbated by the fact that many graduates are finding it difficult to find well-paying jobs, which has spiraled into incredibly high rates of loan delinquency: More than one out of every 10 loan recipients is unable to keep up with payments. The Brookings Institute estimates that nearly 40 percent of borrowers will default by 2023. These are sobering statistics, and it’s important that borrowers be fully aware of the risks and benefits associated with debt of all kinds, including student loans.

The Benefits of Investing in a College Degree

Despite the burden that comes with debt, there are undeniable long-term benefits to earning a degree. In our skills-based economy, it is no surprise that a person with a bachelor’s degree will earn significantly more than a person with only a high school diploma. It has been estimated that a bachelor’s degree increases a person’s average lifetime earnings by $2.8 million.

And the more degrees someone holds, the more their earning potential increases. Studies indicate that earning a graduate degree could triple a person’s expected income. But in the near-term, the financial stress of loan delinquency, deferred consumption, and lower net worth is real.

While the buck ultimately stops with each of us when it comes to our own financial decisions, the student loan quagmire is chiefly the product of federal policy. Federal laws prohibiting sound commercial lending practices and states setting tuition rates high enough to guarantee they’re able to absorb all the federal money they can are complicit in this widespread problem.

Bad Diagnoses Lead to Bad Prescriptions

Rather than addressing the underlying problems of federal financial aid and rising public college tuition, politicians like Senators Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders are offering politically expedient ideas. Sen. Warren proposes debt cancellation of up to $50,000 to more than 42 million people.

Sen. Warren’s plan would eliminate debt for 75% of borrowers with student loans, and federal funding to ensure students attend state college for free. But nothing in life is free. Warren’s sleight-of-hand doesn’t make existing debt or future tuition magically disappear. Rather those costs are passed on to taxpayers. And since college graduates earn roughly twice as much as high school graduates and can expect to be in higher tax brackets, guess who would be paying the taxes for Sen. Warren’s plan.

Why Federal Loans Are Not Like Commercial Loans

To understand the federal student loan mess, it is necessary to understand some details about the loans that are at the center of the issue. The federal government provides a few types of loans, but the largest share of student debt comes from subsidized and unsubsidized federal loans.

In the case of a subsidized loan, the Department of Education pays the interest on the loan while the student is in school and for six months thereafter. A student can qualify for this type of loan whether or not they are creditworthy or have the ability to repay the loan.

In typical commercial lending, a bank would not offer a loan to an individual who didn’t hold a reasonable promise of being able and willing to repay it. This harkens back to 2008 when the US housing market collapsed because of irresponsible lending practices and the belief that everyone—no matter their financial situation—should own a home. It should be no surprise, then, that some economists predict a similar implosion of the student loan market. In other contexts, this would be called predatory lending.

The State’s Role in Tuition Inflation

The second contributor to these financial aid troubles is ballooning state college tuition rates. State legislatures and state institutions set public college rates, so these state officials should be held accountable to provide lower-cost alternatives. One lower-cost alternative to traditional on-campus programs would be to offer a basic skills-based college curriculum online at-cost, i.e., based on the marginal cost of providing downloadable lecture videos and similar programming.

While the total cost to a student of an online degree currently tends to be less than a traditional degree, the tuition is often the same. By offering video of select classes, schools could unlock the value of their existing educational resources and expand access to more students. However, state schools are largely immune from market discipline, which encourages cost-cutting and leveraging economies of scale. Instead of reducing operating costs and tuition prices, state schools soak up the flow of federal loan dollars.

On the finance side, state universities could offer their own alternative to federal student loans. Take, for instance, the market-oriented model of Purdue University and offer income sharing agreements (ISAs). Income sharing agreements allow consumers to pay off a debt by sharing a portion of the student’s income with the lender for a set number of years. Instead of a loan, ISAs allow investors to take “equity” in a student’s future earnings for a period of time.

The problem with the financial aid predicament is that market discipline has been eliminated from state college education and federal financial aid. Public colleges aren’t going to be privatized and run like for-profit businesses any time soon. However, by applying market-based innovations and lessons from the private sector to state colleges, it may be possible to expand access to state college, offer alternative financing arrangements (like income sharing agreements), and reduce the cost of college through technology and economies of scale.

Doug McCullough

Doug McCullough is Director of Lone Star Policy Institute.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.