“[Bitcoin] won’t end well, it’s a fraud…worse than tulip bulbs…[but] if you were a drug dealer, a murderer, stuff like that, you are better off doing it in bitcoin than U.S. dollars.” ~ Jamie Dimon: CEO, JP Morgan

Headline: JPMorgan Guilty of Money Laundering, Tried To Hide Swiss Regulator Judgement ~ via Cointelegraph

Given the current, latest successive series of spikes to all-time highs for Bitcoin, the detractors are working overtime to make the case that the crypto-currency is a Ponzi, a scam, a phantasm, or, at the very least, a bubble. Oddly, many of these same detractors spend a lot of time cheerleading “the other bubble,” that everything-bubble, stocks, bonds, real estate, even ETFs of ETFs, you name it.

It’s easy to make superficial apples-to-screwdrivers comparisons about why Bitcoin is doomed to fail until you really take some time to look into it. When I was first exposed to the idea back in 2013 and researched it, I realized that “this really is different,” and the reason why was because of something John Kenneth Galbraith had once written which (until then) had invariably held up as true. In “A Short History of Financial Euphoria” Galbraith said:

The world of finance hails the invention of the wheel over and over again, often in a slightly more unstable version. All financial innovation involves in one form or another, the creation of debt secured in greater or lesser adequacy by real assets. (emphasis added)

When one looks at history, this accurately maps every financial bubble from Tulipmania (which we will debunk as a suitable metaphor for Bitcoin shortly) right up to 2008 and beyond.

However one place where it isn’t applicable is the phenomenon of Bitcoin. Crypto-currencies, at least at present, have no leverage and are near-impossible to purchase on credit. In other words, if asset bubbles get that way largely through leverage, and there is comparatively no leverage in Bitcoin, then something else has to be driving it.

That said…

The Price of Bitcoin is a Side Show.

Granted, at the moment it’s a very exciting sideshow for those who are on the train. A long-time customer emailed me as I was writing this asking, “At what point has easyDNS’ profits from accepting and holding bitcoin exceeded the actual operating profits of the company?” I had never considered that, but some quick math revealed that even after cashing a chunk out to buy gold (not my greatest trade), that happened last year.

But the price action around this isn’t what is exciting about Bitcoin and the crypto-currency revolution. What is exciting is that the centralized, bankster-controlled monopoly over the issuance of money itself is finished. It’s over. Even if they successfully manage to co-opt some major crypto-currencies or issue their own, Gresham’s Law will assert itself as capital managers will select a truly decentralized crypto-currency wherein they control, or have the option to control, their own private keys to safely store their wealth while they’ll use the government version to pay taxes, etc.

Whatever state-issued “digital cash” comes out in the near future, I’m suspecting it will be centralized with mandatory private key custody or escrow. When that happens, it shouldn’t even be called crypto-currency. Call it something else like “pseudo-crypto” or “fauxcoin” to differentiate.

Given the mostly bad analogies and unfounded criticisms being leveled at Bitcoin, let’s first take a serious look at what Bitcoin isn’t. Then, in Part II we’ll look at what it is and why it’s different.

What Bitcoin Isn’t

“Backed by nothing”

This is the go-to criticism for people who simply don’t understand that crypto-currencies are based upon mathematics, zero-trust, open-source, and consensus. They think that bitcoins can simply be created “at will” and are backed by nothing.

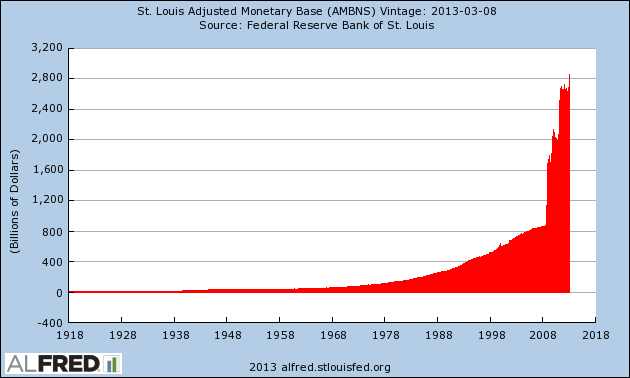

They also say that as if the world’s reserve currency, the US dollar, isn’t, literally, “backed by nothing” and hasn’t been since 1971; and as if it can’t be created at will, which it most certainly has, with a vengeance.

Source: St. Louis Fed

Indeed, as Galbraith continued in our earlier passage:

This was true in one of the earliest seeming marvels: when banks discovered that they could print bank notes and issue them to borrowers in excess of the hard-money deposits in the banks’ strong rooms.

All fiat currencies today really are backed by nothing and can be created at will (that’s what the word “fiat” actually means), and perhaps unbeknownst to many, we are right now in a protracted, global currency war. Every nation is “racing to the bottom,” trying to devalue their currency against their trading partners so they can:

- give their exporters a competitive advantage

- pull stronger currencies in to make money on the exchange, and

- service their ever expanding debts back with devalued, cheaper currency

This is why everybody’s purchasing power is going down despite tenured academics and central bankers incessantly complaining about “low inflation” and political spokesmodels always talking up a “strong currency.”

Bitcoin Isn’t: “Backed by nothing.”

What Is? The USD and every other fiat currency in the world.

“Bitcoin is a Ponzi”

The idea that Bitcoin or most crypto-currencies are “a Ponzi” is easily debunked by understanding what a Ponzi actually is.

As observed in CryptoAssets (Burniske & Tartar, 2017), it’s very simple: new investors pay old investors.

It is important to realize that in a Ponzi, the earlier investors are literally paid with funds being injected by the new investors in a “flow through” fashion (as distinct from later investors having to pay higher prices to earlier ones to induce them to part with an asset).

As long as the number of new investors and, thus, the influx of funds is growing at a rate faster than the payouts to the earlier investors, the Ponzi scheme thrives. When the expected payouts exceed the rate of input, it dies.

One doesn’t have to look very far to find mechanisms that fit the definition exactly: Social security programs are all classic ponzis. The demographic reality of today is that with the entry of the “Baby Boomer” generation into retirement, given that the subsequent generations are so much smaller in size, additionally penalized by falling real wages, growing taxation, decaying purchasing power of their money, and returns on any savings they can eek out suppressed into negative nominal yields — this Ponzi is in its terminal phase.

(Given that these exacerbating headwinds which face later generations can be summed up with the phrase “financial repression,” it is only logical that capital would “flee” to some asset or currency which appears resistant to them.)

Granted, the current ICO craze probably includes some Ponzis. The Cryptoassets book describes the OneCoin Ponzi as well as how to spot a Ponzi in crypto-currencies. I would have been hesitant to even call OneCoin a crypto-currency at all. It wasn’t open-source and had no public blockchain.

In Bitcoin and other true crypto-currencies, early holders are not receiving bitcoin from later entrants. In fact, quite the opposite is happening. Later entrants must entice earlier ones to part with their bitcoin. Since bitcoin cannot be created at will, it must be mined at a rate that drops over time (this year approximately 640K new bitcoin will be mined, about 3.8% of the total supply).

Demand for bitcoin is simply outstripping the supply of new coins being mined (for reasons we will discuss in Part II). If said price action rises dramatically (like, for example, Bitcoin suddenly became the highest performing asset class in the world) then a feedback loop would occur. Ever higher prices would be required to induce earlier holders to sell.

Bitcoin Isn’t: A Ponzi

What Is? Social Security

Tulipmania

What is described above is the same dynamic that occurs in any “bull market,” as buying begets more buying and “fear of missing out” kicks in. It is said that one of the most accurate gauges of “happiness” correlates closely to how much wealth one has when compared to one’s brother-in-law. Alex J Pollock describes it in Boom and Bust: Financial Cycles and Human Prosperity, as “The disturbing experience of watching one’s friends get rich.”

The trick would be to have some understanding of when a strong bull market has crossed into bubble territory. One of the more popular analogies for Bitcoin is Tulipmania: the financial bubble that occurred in 1630s Amsterdam with none other than tulip bulbs. Bitcoin is compared to Tulipmania so often that I decided to take a closer look at Tulipmania to see if the comparison was valid.

What I found was that most of what we know today about Tulipmania is superficial and self-referential, deriving primarily Charles Mackay’s chapter on Tulipmania in his seminal “Extraordinary Delusions and the Madness of Crowds” (1841). It is a scant 9 pages an purely anecdotal, describing ridiculous prices paid by the otherwise pragmatic and level-headed Dutch, and then it all just blew up like all bubbles do.

Finally I found Anne Goldgar’s Tulipmania: Money, Honor and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age, which is the most in-depth investigation of the rise and subsequent fall of Tulipmania extant today. In it we learn about the circular references that went on to inform our present time about Tulipmania:

If we trace these stories back through the centuries, we find how weak their foundations actually are. In fact, they are based on one or two contemporary pieces of propaganda and a prodigious amount of plagiarism. From there we have our modern story of tulipmania.

She traces the lineage of MacKay’s chapter:

Mackay’s chief source was Johann Beckmann, author of Beytrage zur Geschichte der Erfindungen, which, as A History of Inventions, Discoveries and Origins, went through many editions in English from 1797 on. Mackay’s chief source was Beckmann was concerned about financial speculation in his day, but his own sources were suspect.

He relied chiefly on Abraham Munting, a botanical writer from the late seventeenth century. Munting’s father, himself a botanist, had lost money on tulips, but Munting, writing in the early 1670s, was himself no reliable eyewitness. His own words, often verbatim, come chiefly from two places: the historical account of the chronicler, Lieuwe van Aitzema in 1669, and one of the longest of the contemporary pieces of propaganda against the trade, Adriaen Roman’s Samen-spraech tusschen Waermondt ende Gaergoedt (Dialogue logue between True-mouth and Greedy-goods) of 1637. As Aitzema was himself basing his chronicle on the pamphlet literature, we are left with a picture of tulipmania based almost solely on propaganda, cited as if it were fact. (emphasis added)

Goldgar helps the reader in pursuit of truly understanding Tulipmania by rewinding to the late 1590s when there were no tulips in what is now Holland, or, in fact, the whole of Europe. Gardens were purely functional, designed for growing food, herbs, or medicinals. Then tulips and other curiosities began coming into the country and Europe from merchant vessels trading in the Mediterranean and Far East.

The “flower garden” arose for the first time, and it was spectacular — giving rise to an entire movement of collectors and aficionados whom, in the early days, were, as a rule, well-to-do. In later years, more people sought out, and then speculated in, the tulip trade not only to profit, but to lay their own claims on what they perceived to be a higher economic class or status.

At the risk of over simplifying her work, the tulip trade became intertwined and inseparable from, art.

At the risk of over simplifying her work, the tulip trade became intertwined and inseparable from, art.

The collecting of art seemed to go with the collecting of tulips. This meant that the tulip craze was part of a much bigger mentality, a mentality of curiosity, of excitement, and of piecing together connections between the seemingly disparate worlds of art and nature. It also placed the tulip firmly in a social world, in which collectors strove for social status and sought to represent themselves as connoisseurs to each other and to themselves.

The more I delved into understanding Tulipmania, the more I couldn’t escape thinking that the analogy was much more applicable to a different “asset class” which did enjoy a momentous bubble in recent times, but it wasn’t Bitcoin or crypto-currencies. To belabor my point, Bitcoin was impelled not by art, beauty, or any semblance of collectibility, but emerged primarily as a resistance to financial repression.

Something that was driven by uniqueness and fostered an aristocratic in-club all its own and, until recently, enjoyed stratospheric price action was the aftermarket in domain names. This isn’t the place to conduct a post-mortem on that bubble, but suffice it to say that the distinct characteristics of domain names more closely resembled that of tulip bulbs than Bitcoin does. (For the reader interested, I have written at length about the domain aftermarket here and here.)

Bitcoin Isn’t: Tulipmania

What Is? Domain names.

If Bitcoin isn’t a digital fiat backed by nothing, nor a Ponzi, nor Tulipmania, then what is it? Why has this come out of literally nowhere to become the strongest performing and fastest growing asset/currency in the world?

When I started writing this article, I wasn’t sure myself. I had to go back through my library and look at history and try to find some antecedent for what was happening. After looking back through the origins of money itself and working forward, I still wasn’t any closer to a mental model that “worked.”

Then, around 2 a.m. the other night, I woke up with the idea that I was looking in the wrong place, and it hit me with such force that I had a hard time getting back to sleep — even though I had made an “off the cuff” tweet that captured the basic idea of it a few weeks earlier (which I can’t find now).

I’ll take you through it in Part II. But in the meantime, I’ll leave you with another megabank CEO whose take on all this is very different from Jamie Dimon’s. Goldman Sachs’ CEO Lloyd Blankfein here muses on why it’s entirely plausible that money may evolve from being based on fiat to being based on consensus. These are some truly extraordinary remarks coming from a man in his position.

This article first appeared on Hackernoon

Mark E. Jeftovic easyDNS co-founder & CEO. Guerrilla-Capitalism.com

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.