Ryan Crownholm is a self-described “serial entrepreneur” and the founder of a California-based business called MySitePlan.com. Founded in 2013, the business creates unofficial “site plans” for various clients using publicly available imagery. Hotels and resorts will sometimes use the plans as maps for their guests. Homeowners and contractors often use the plans in their permit applications when they are preparing to make minor changes to a property, such as building a shed or removing a tree.

Over the years, MySitePlan.com has built a strong reputation for itself, and customers are consistently impressed with the quality of the work and the short turn-around times (often within 24 hours).

“I had the first draft within 8 hours and they made changes to accommodate what the city needed. Good service!” writes one recent reviewer. “Amazing service! So incredibly quick! I will recommend this company to anyone in need of a site plan,” writes another.

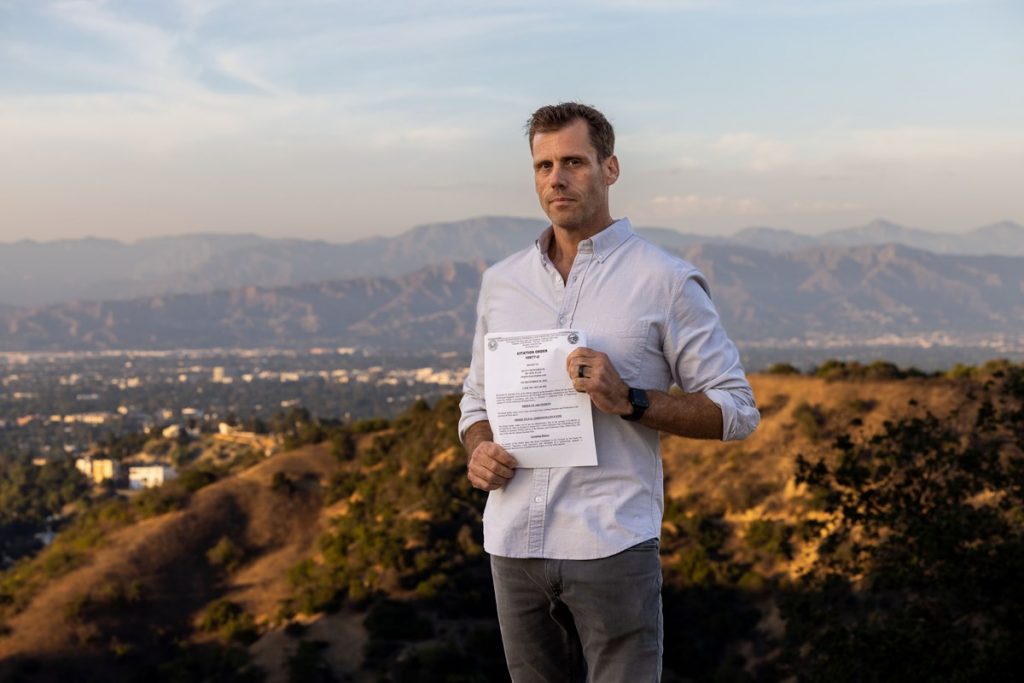

Crownholm and his customers are certainly happy the business has been successful, but it seems not everyone feels this way. In December 2021, Crownholm was given a citation from the California Board for Professional Engineers, Land Surveyors, and Geologists. The order demanded that he “cease and desist from violating” the law and pay a fine of $1,000.

What was Crownholm’s crime? According to the Board, Crownholm and his company were illegally practicing land surveying without a license. In the Board’s view, “preparing site plans which depict the location of property lines, fixed works, and the geographical relationship thereto falls within the definition of land surveying,” and thus requires a license.

It’s worth noting that MySitePlan.com never claimed to create official land surveys by licensed surveyors. In fact, a banner at the top of their website plainly states, “This is not a legal survey, nor is it intended to be or replace one.”

Now, it’s tempting to say Crownholm should just get a license and move on, but it’s not that simple. Obtaining a land surveying license is an arduous process. In the state of California it requires six years of higher education and practical experience, passing four exams, and earning references from four existing licensees.

So rather than getting a license or shutting down his business, Crownholm has chosen to take the Board to court. On September 29, Crownholm joined with the Institute for Justice to file a federal lawsuit against the Board, claiming that the regulation violates his First Amendment right to free speech.

“California regulators are strangling entrepreneurs, like me, with red tape even though customers are pleased with the valuable services we provide,” Crownholm said. “Prosecuting my company hurts homeowners, contractors, landscapers, farmers, wedding venues and others who depend on my service.”

“California’s regulations go far beyond what other surveying regulators think is appropriate,” said Institute for Justice Attorney Mike Greenberg. “This is yet another example of an established industry using the government to shut down popular, innovative competition. If read literally, California’s laws could harm services everyday people use such as Uber and Google Maps. It would even criminalize drawing a makeshift map on a napkin to help a lost tourist find the way to their destination.”

A Mysterious Motive

The question on everyone’s mind, of course, is why? Why would this regulatory board go after an entrepreneur when he’s clearly not in the business of official land surveying?

The simplest explanation is that they’re just really eager to enforce the law to the letter. That seems to be the argument they’re going with. But if that’s the case, why don’t they also crack down on the homeowners and contractors who regularly make identical site plan drawings? As the Institute for Justice press release notes, “California’s own building departments teach [unlicensed] homeowners and contractors how to make the exact same drawings Ryan makes.”

So if litigiousness is the goal, why single out MySitePlan.com?

Perhaps they think he’s taking safety shortcuts, but that makes no sense. There’s nothing dangerous about what he’s doing. Maybe they’re concerned he’s a fraud, and that the quality of his product doesn’t match what he promises? It’s possible, but a quick glance at his glowing reviews ought to set the record straight on that. Maybe they think he’s misrepresenting himself, pretending to have a license when he really doesn’t? Again, that makes no sense. He’s very explicit on the website that he doesn’t do official land surveys.

Perhaps they just think it’s unfair that everyone else has to go through an arduous licensing process while he gets to avoid it despite doing very similar work. That would be understandable, but if it was really just about fairness, wouldn’t it make more sense to push for scrapping the burdens on everyone else rather than imposing those burdens on him?

None of these motives make much sense.

There’s another possible motive, however, and that’s the malicious one. Perhaps the regulators were simply looking to protect licensed surveyors from competition. After all, less competition means higher prices and more business for those who have jumped through the hoops. I’m sure many licensed surveyors weren’t particularly happy to see MySitePlan.com taking away potential clients.

Even assuming the absolute best of intentions, one must admit the decreased competition would be at the very least a convenient side-benefit for the established special-interests.

Oh, and did I mention that the the guy who issued the citation—Richard B. Moore, the Board’s Executive Officer—is himself a licensed land surveyor?

Bootleggers and Baptists

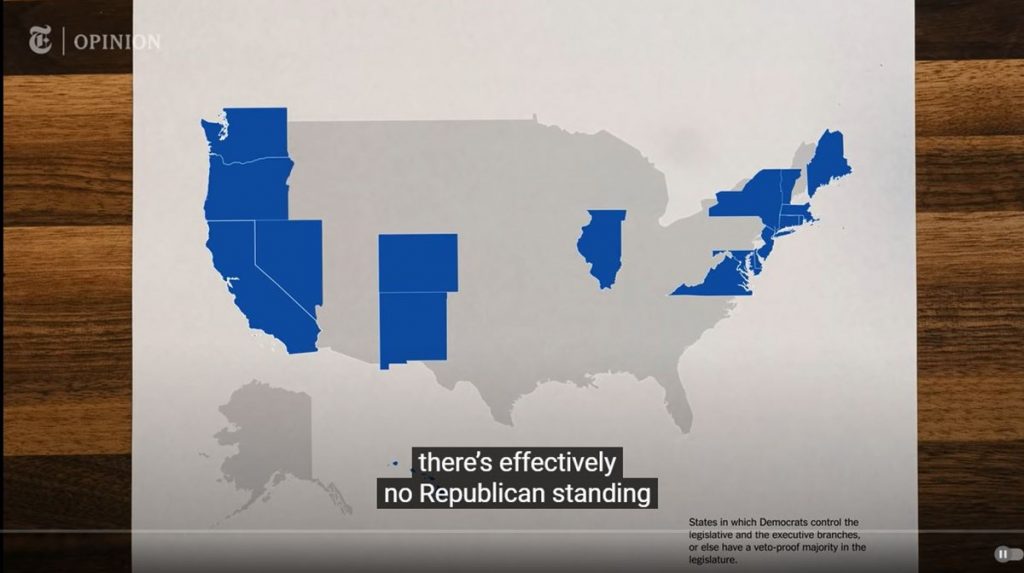

This isn’t the first time entrepreneurs have been impeded by these kinds of regulations. Occupational licensing requirements like this are ubiquitous, not just for doctors and engineers, but also for jobs that have little to do with safety like hair braiding.

Every industry has a similar story. Decades ago there was an accident, maybe a series of accidents, or some fraudulent practitioner. As a result, people pressured the government to “do something,” and the government responded by creating a licensing scheme.

The thinking is pretty straightforward. We make it illegal for someone to practice a trade unless they have a government-approved license, and the government only gives licenses to people who can prove they are trustworthy and capable. Ostensibly, the system protects consumers. But that’s just the official narrative.

Whether by design or by accident, licensing laws also have the effect of limiting competition, resulting in higher prices and fewer options for consumers.

I say “by design or by accident” because it isn’t always clear what the intentions were of the people who promoted these schemes. Though it’s nice to think they were all motivated by an altruistic desire to help consumers, it’s more realistic to see this as a classic “Bootlegger and Baptist” alliance—a phrase that was coined by economist Bruce Yandle in a 1983 paper in reference to the Prohibition era.

The “Baptists” are the true believers. They are motivated, in their desire for government regulation, by genuine—though often misguided—concern for consumers. The “Bootleggers” are the special-interest groups who stand to benefit should these laws pass. The strategy of the Bootlegger is simple and surprisingly effective: simply paint yourself as a Baptist and push for the regulations with altruistic arguments, even though your real goal is to hurt your competitors.

“A carefully constructed regulation can accomplish all kinds of anticompetitive goals,” Yandle wrote, “while giving the citizenry the impression that the only goal is to serve the public interest.”

In 2014, Yandle expanded on his theory in a book titled Bootleggers and Baptists that he co-authored with his grandson Adam Smith (not to be confused with the original Adam Smith). In a review of the book, economist Art Carden summarized the theory rather succinctly.

“Public policies…emerge because a moral constituency (the Baptists) and a financial constituency (the bootleggers) come together in support of the same policies,” Carden wrote.

Quoting the book, Carden notes that special interests looking to pass anti-competitive regulations often seek out “a respectable public-spirited group seeking the same result [in order to] wrap a self-interested lobbying effort in a cloak of respectability.”

Carden goes on to identify occupational licensing in particular as a good example of the Bootleggers and Baptists theory playing out in real life.

The Case against Occupational Licensing

While the drawbacks of occupational licensing laws are difficult to deny, some may still have reservations about abolishing them. If we let just anyone practice these professions, wouldn’t there be a proliferation of fraudulent and dangerous practitioners? Isn’t that why these laws were needed in the first place, to protect us from the evidently disastrous results of free markets?

This is a common line of argumentation, but it’s missing some key nuances. First, it’s important to keep in mind that the mental picture many have of the pre-license market is likely distorted. The special-interest groups pushing for these laws have a strong incentive to exaggerate how bad things used to be; it would be naive to simply take them at their word.

Further, it’s important to remember that people were much poorer back when these laws were first introduced, so we shouldn’t be surprised that the general standard of living—including the quality and safety of services available on the market—was far lower than it is today. The fact that “things used to be bad” is much more a reflection of our ancestors’ relative poverty than an indictment of unregulated markets.

For another point, clearly it’s tragic when people get injured or killed because of incompetent workers, but there is always a trade-off between cost and safety. Sometimes people prefer slightly less safe options (such as workers with less training) because those options are cheaper. And if that’s a risk they want to take, we’re only making them worse-off by taking that option away.

The other thing to consider is that businesses that are downright dangerous or fraudulent get weeded out very quickly. As a business owner, if you don’t provide a reasonable level of quality and safety in your products, you’ll be out of business in no time. Since entrepreneurs know this, they have a strong incentive to avoid hiring dangerous and fraudulent workers. Economists call this the discipline of continuous dealings. This, not licensing, is the reason we can trust most of the businesses we patronize.

Besides, there are plenty of ways to ensure product safety and quality that don’t involve licensing laws. Workers can get voluntary certifications and consumers can look at reviews to help them decide who they can trust. Just think about MySitePlan.com and their reviews we saw earlier. Did you really need them to have a license to know they were a trustworthy business?

What Consumers Really Need

Though government licensing may seem like a good way to protect consumers, the reality is that these schemes unnecessarily restrict competition, with fewer options and higher prices being the inevitable result. In other words, they mostly end up hurting the very consumers they were supposed to help.

The best way to help consumers is to give them lots of choices and a rigorously competitive market. And the way to achieve that is not by protecting established special interests from new players. It’s by letting the Ryan Crownholms of the world compete.

This article was adapted from an issue of the FEE Daily email newsletter. Click here to sign up and get free-market news and analysis like this in your inbox every weekday.

Patrick Carroll

Patrick Carroll has a degree in Chemical Engineering from the University of Waterloo and is an Editorial Fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.