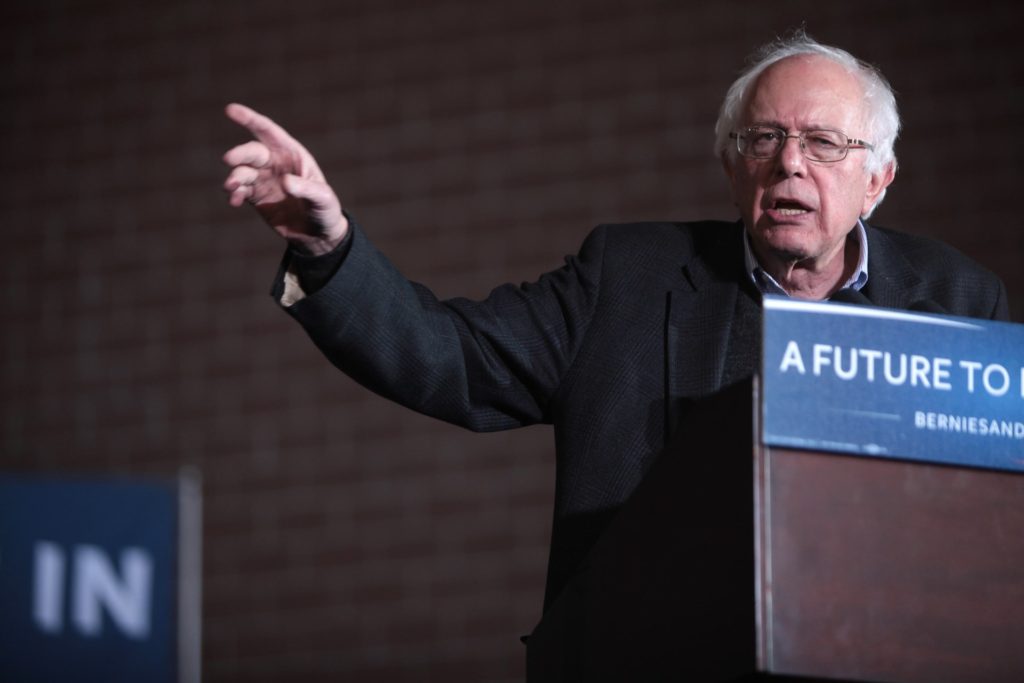

Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders doubled down when asked about his universal jobs guarantee included in last Tuesday night’s Democratic debates. “Damn right, we will” create jobs for every adult in the workforce, he insisted.

But Sanders’s promise of jobs for all, however appealing it may sound, aims at the wrong target.

In what Henry Hazlitt described as “the fetish of full employment” in his 1946 classic Economics in One Lesson, Hazlitt declared that the goal of full employment is fool’s gold.

Prioritize Production to Create Jobs

Instead of focusing on policies to maximize employment, Hazlitt declared, “We can clarify our thinking if we put our chief emphasis where it belongs—on policies that will maximize production.”

Why focus on maximizing production rather than jobs?

Creating jobs is easy. As Hazlitt wrote, “Nothing is easier to achieve than full employment, once it is divorced from the goal of full production and taken as an end in itself.”

Economist Milton Friedman was once traveling overseas and spotted a construction site in which the workers were using shovels instead of more modern equipment like bulldozers. When his host responded that the goal was to increase the number of jobs in the construction industry, Friedman replied, “Then instead of shovels, why don’t you give them spoons and create even more jobs?”

The key to a healthy economy, conversely, is increasing production using less and less labor. Trying to exclusively “create jobs” or provide universal job guarantees can lead to perverse incentives like restricting workers’ access to productivity-enhancing capital goods in order to require more workers than necessary to produce goods and services.

Under a plan like Sanders’s, a project would be considered more successful the more people it employed relative to the value of the product of the work performed. In short, success would be measured by making labor less and less efficient.

How can it benefit society to demand, say, 200 workers build a bridge that could have been built using 100?

As Hazlitt wrote,

The economic goal of any nation, as of any individual, is to get the greatest results with the least effort. The whole economic progress of mankind has consisted in getting more production with the same labor.

The Power of Creating Value

Value creation, not a measure of employment, is the true measure of economic well-being. Imagine if society could enjoy a luxurious standard of living that requires only half of the people to work to provide it.

Hazlitt asked,

The real question is not how many millions of jobs there will be in America ten years from now, but how much we produce, and what, in consequence, will be our standard of living?

Moreover, Hazlitt dismissed concerns that labor-saving capital goods would cause significant unemployment. Indeed, he argued the opposite. “[O]ur real objective is to maximize production. In doing this, full employment—that is, the absence of involuntary idleness – becomes a necessary byproduct,” he wrote.

Prioritizing employment over productivity puts the cart before the horse. He noted,

[P]roduction is the end, employment merely the means. We cannot continuously have the fullest production without full employment. But we can very easily have full employment without full production.

And the labor that is freed up due to productivity gains can be employed in satisfying other needs and wants of consumers, often new or not-yet imagined desires.

As Steve Jobs said to Business Week in 1998: “It’s really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.”

If labor is tied up using spoons in make-work, government-sponsored “job guarantee” jobs, who will produce the next big thing?

Government jobs programs will not only tend to reward less efficient labor but will also tend to tie the labor force to current modes of production, allowing less opportunity for life-changing innovations.

In sum, high levels of employment do not necessarily mean prosperity. As Hazlitt concluded, “Primitive tribes are naked, and wretchedly fed and housed, but they do not suffer from unemployment.”

Bradley Thomas

Bradley Thomas is creator of the website Erasethestate.com and is a libertarian activist and writer with nearly 15 years experience researching and writing on political philosophy and economics.

Follow him on Twitter: ErasetheState @erasestate

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.