One thing everyone remembers about the October Revolution of 1917, which brought Vladimir Lenin to power, was that the Bolsheviks toppled the tsar, an incompetent monarch who had run Russia into the ground.

The problem is that’s not what happened.

First, the event happened on November 7, according to the modern calendar, not in October. Second, and more importantly, Lenin and his insurgents did not overthrow the tsarist regime. Few seem to remember that Tsar Nicholas II had been dealt with in February 1917. When Lenin cooly ordered Nicholas and his family to be executed without a trial in Yekaterinburg in July 1918, the Tsar had been out of power for more than a year. What the Bolsheviks actually toppled was something resembling a modern democracy with an elected parliament and government.

That the rise of 20th-century socialism began with a falsehood is fitting since its modern foundation is also built largely on fiction.

The Realities of Socialism

More than a century after the Bolsheviks took power—and 30 years after their experiment failed for all the world to see—the misconceptions continue.

New surveys show as many as 70 percent of millennials would vote for a socialist, no doubt because they’ve heard how equitable and fruitful the system is. Few today seem to understand just how awful life under socialism was.

As someone born and raised on the wrong side of the Berlin Wall, let me tell you: Everyday life was bad. I’m not talking about secret police, censorship, forced adulation, or KGB agents among students (my mother was labeled an “anarchist,” which meant she had no prospects for a career). Even the most mundane activities, like buying food, were a challenge. Shortages, deficits, and lines, lines, lines. If you saw a queue, you‘d automatically join it without asking what people were queueing for. It must have been good!

“Good“ had a completely different meaning under socialism. The absolute majority of consumer goods were awful knockoffs of Western merchandise. The waitlist to buy a car was around seven years. Permission to buy a color TV was often granted by trade union raffle. Those with connections to the Communist Party or union bosses were given preference.

Anyone who studied economics might be tempted to think that perhaps goods were mispriced; the prices were set too low, demand exceeded supply, and therefore—queues. But the prices the socialist government set for consumer goods were ridiculously high. A TV cost something like 600-700 roubles, while your average monthly salary was about 150 roubles. Modern estimations of how long one had to work to purchase consumer goods in the Soviet Union run as follows: a TV was 713 hours (4.4 months), a refrigerator 378 hours (2.3 months), a raincoat was 77 hours (nearly two weeks), shoes were 33 hours (nearly a week).

A typical American, on the other hand, had to work 86 hours to afford a TV, 83 hours for a refrigerator, and eight hours for shoes.

Perhaps under socialism there was more income equality? Actually, no. Sure, you can measure official income inequality, which was around 0.3 GINI—a method of measuring income inequality—not much different from current Western countries.

But how do you factor in things like special shops for Party members, which regular people were not allowed to enter? Or raffles where Party members were given preference?

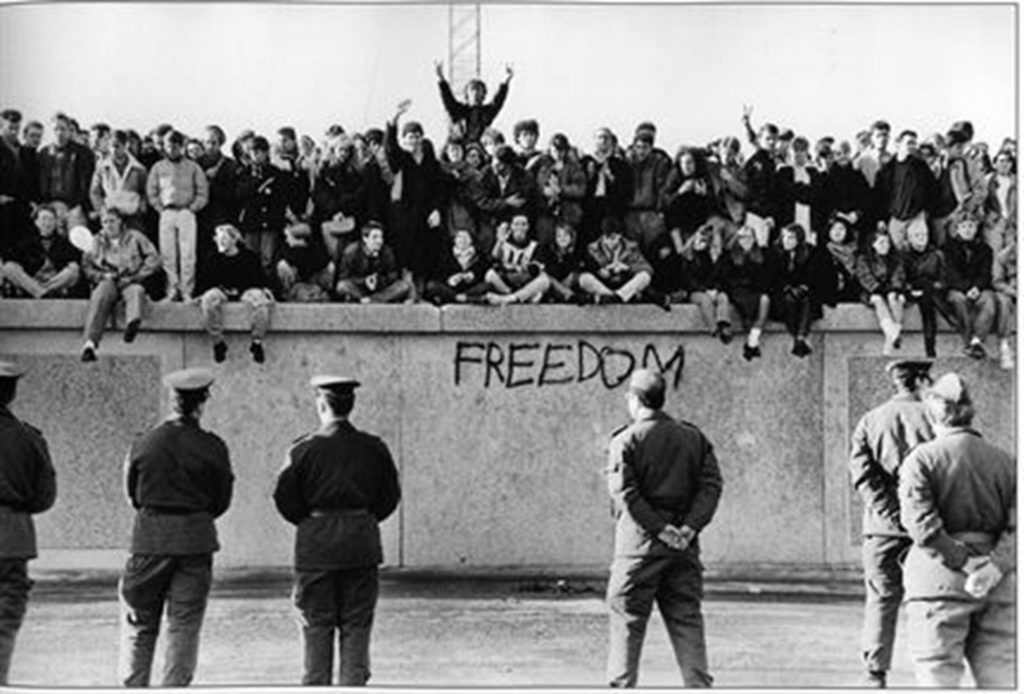

Why People Tore the Wall down with Their Bare Hands

What do these recaps of high school history and memories of those who actually lived under socialism have to do with today? Call it a reaction to horror when one hears elected American politicians spouting statements that socialism is a good thing—that America needs socialism. It‘s like being a very old German and being told that dressing young hooligans in brown shirts and setting them loose on the streets will improve public safety. It’s like being a survivor of Chernobyl and hearing that nuclear safety is for hippies.

Socialism was, is, and will continue to be an utter failure in everything except keeping people behind Berlin Walls, iron curtains, and barbed wire. Poverty, inequality, disregard for human dignity and human life—that was the everyday life under socialism, not brotherhood and equality.

There is a reason people tore down the Berlin Wall with their bare hands the moment they realized they would not be shot. Let’s not repeat these mistakes 30 years later.

Zilvinas Silenas

Zilvinas Silenas became President of the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) in May 2019. He served from 2011-2019 as the President of the Lithuanian Free Market Institute (LFMI), bringing the organization and its free-market policy reform message to the forefront of Lithuanian public discourse. In that role, he and the LFMI won two prestigious Templeton Freedom Awards (2014 and 2016) for Municipality Performance Index and the Economics in 31 Hours textbook, now used by 80% of Lithuanian high school students. Silenas holds degrees in economics from Wesleyan University and the ISM University of Management and Economics, and has served in numerous teaching and advisory roles. He and his wife Rosita live in Atlanta where they enjoy exploring the outdoors, attending social functions, and the occasional pickup basketball game.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.