As a policy wonk, I mostly care about the overall impact of government on prosperity. So when I think about the effect of red tape, I’m drawn to big-pictures assessments of the regulatory burden.

Here are a few relevant numbers that get my juices flowing.

- Americans spend 8.8 billion hours every year filling out government forms.

- The economy-wide cost of regulation reached $1.75 trillion in 2010.

- For every bureaucrat at a regulatory agency, 100 jobs are lost in the economy’s productive sector.

- A World Bank study determined that moving from heavy regulation to light regulation “can increase a country’s average annual GDP per capita growth by 2.3 percentage points.”

- Regulatory increases since 1980 have reduced economic output by $4 trillion.

- The European Central Bank estimated that product market and employment regulation has led to costly “misallocation of labour and capital in eight macro-sectors,” and also found that reform could boost national income by more than six percent.

But one thing I’ve learned over the years is that I’m not normal.

Most people don’t get excited about these macro-type calculations.

Instead, they’re far more likely to get agitated by regulations that make their daily lives a hassle. Such as:

- Inferior light bulbs

- Substandard toilets

- Inadequate washing machines

- Crummy dishwashers

- Dribbling showers

- Dysfunctional gas cans

I certainly can sympathize. It’s galling that the clowns in Washington have made our existence less pleasant.

Most people also are quite responsive to anecdotes about red tape. Simply stated, big-picture numbers are like a skeleton, while real-world examples put meat on the bones.

Today, let’s look at some absurd examples of the regulatory state in action.

We’ll start with bone-headed pizza regulation, as explained by the Wall Street Journal.

FDA released guidance for posting calorie disclosures at restaurants with more than 20 locations, and the ostensible point is to help folks choose healthier foods. The regulations…are an outgrowth of the 2010 Affordable Care Act… The reason some restaurants have spent years fighting these rules is not because executives lay awake at night plotting how to make Americans obese. It’s because the rules are loco. …Take pizza companies, which have to display per slice ranges or the number for the entire pie. Calories vary based on what you order—the barbarians who put pineapple on pizza are consuming fewer calories than someone who chooses pepperoni and extra cheese. But the number of pepperonis on a pizza depends on the pie’s size and whether someone also adds onions and sausage. ..The rules are so vague that companies could face a crush of lawsuits, which will be abetted by this “nonbinding” FDA guidance.

By the way, you won’t be surprised to learn that academic researchers have found these types of rules have no effect on consumer choices.

A systematic review and meta-analysis determined the effect of restaurant menu labeling on calories and nutrients…were collected in 2015, analyzed in 2016, and used to evaluate the effect of nutrition labeling on calories and nutrients ordered or consumed. Before and after menu labeling outcomes were used to determine weighted mean differences in calories, saturated fat, total fat, carbohydrate, and sodium ordered/consumed… Menu labeling resulted in no significant change in reported calories ordered/consumed… Menu labeling away-from-home did not result in change in quantity or quality, specifically for carbohydrates, total fat, saturated fat, or sodium, of calories consumed among U.S. adults.

Shocking, just shocking. Next thing you know, someone will tell us that Obamacare didn’t lower premiums for health insurance!

For our second example, we have a surreal story out of California.

A farmer faces trial in federal court this summer and a $2.8 million fine for failing to get a permit to plow his field and plant wheat in Tehama County. A lawyer for Duarte Nursery said the case is important because it could set a precedent requiring other farmers to obtain costly, time-consuming permits just to plow their fields. “The case is the first time that we’re aware of that says you need to get a (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers) permit to plow to grow crops,” said Anthony Francois, an attorney for the Pacific Legal Foundation. “We’re not going to produce much food under those kinds of regulations,” he said. …The Army did not claim Duarte violated the Endangered Species Act by destroying fairy shrimp or their habitat, Francois said. …Farmers plowing their fields are specifically exempt from the Clean Water Act rules forbidding discharging material into U.S. waters, Francois said.

Wow, sort of reminds me of the guy who was hassled by the feds for building a pond on his own property. Or the family persecuted for building a house on their own property.

Last but not least, our third example contains some jaw-dropping tidbits about red tape in a New York Times story.

Indian Ladder Farms, a fifth-generation family operation near Albany, …sells homemade apple pies, fresh cider and warm doughnuts. …This fall, amid the rush of commerce—the apple harvest season accounts for about half of Indian Ladder’s annual revenue—federal investigators showed up. They wanted to check the farm’s compliance… Suddenly, the small office staff turned its focus away from making money to placating a government regulator. …The investigators hand delivered a notice and said they would be back the following week, when they asked to have 22 types of records available. The request included vehicle registrations, insurance documents and time sheets—reams of paper in all. …the Ten Eyck family, which owns the farm, along with the staff devoted about 40 hours to serving the investigators, who visited three times before closing the books. …This is life on the farm—and at businesses of all sorts. With thick rule books laying out food safety procedures, compliance costs in the tens of thousands of dollars and ever-changing standards from the government…, local produce growers are a textbook example of what many business owners describe as regulatory fatigue. …The New York Times identified at least 17 federal regulations with about 5,000 restrictions and rules that were relevant to orchards. …Mr. Ten Eyck…fluently speaks the language of government compliance, rattling off acronyms that consume his time and resources, including E.P.A. (Environmental Protection Agency), OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration), U.S.D.A. (United States Department of Agriculture) and state and local offices, too, like A.C.D.O.H. (Albany County Department of Health).

And here’s an infographic that accompanied the article.

Wow. No wonder a depressingly large share of the population prefers to simply get a job as a bureaucrat.

Needless to say, this is not a system that encourages and enables entrepreneurship.

Which is why deregulation is a good idea (and Trump deserves credit for making a bit of progress in this area). We need some sensible cost-benefit analysis so that bureaucracies are focused on public health rather than mindless rules.

And it also would be a good idea in many cases to rely more on mutually reinforcing forms of private regulation.

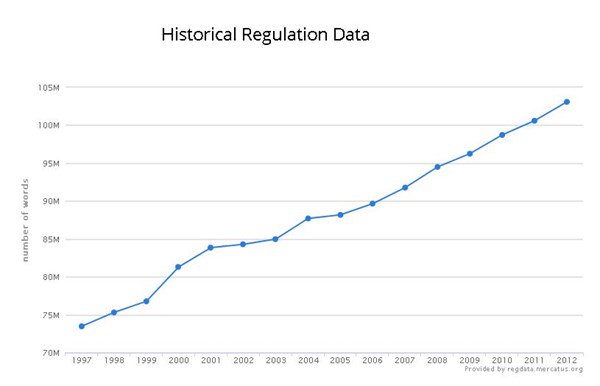

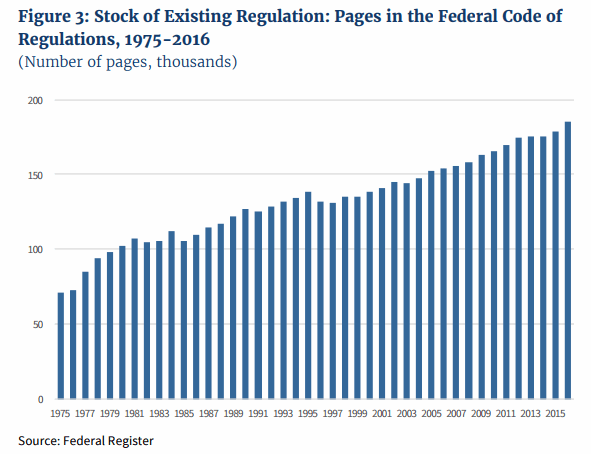

Since I’m a self-confessed wonk, I’ll close by sharing this measure of the ever-growing burden of red tape. I realize it’s not as attention-grabbing as anecdotes and horror stories, but it is very relevant if we care about long-run growth and competitiveness.

P.S. On the topic of regulation, I admit that this example of left-wing humor about laissez-faire dystopia is very clever and amusing.

P.P.S. I’ve used an apple orchard as an example when explaining why a tax bias against saving and investment makes no sense. I’ll now have to mention that the beleaguered orchard owner also has to deal with 5,000 regulatory restrictions.

Reprinted from International Liberty.

Daniel J. Mitchell is a Washington-based economist who specializes in fiscal policy, particularly tax reform, international tax competition, and the economic burden of government spending. He also serves on the editorial board of the Cayman Financial Review.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.