Inflation is commonly defined as “a general increase in prices and fall in the purchasing value of money.” For example, if a six-pack of beers cost $8 last year, but this year the same six-pack costs $16 then the annual inflation rate was 100 percent. This is because the price doubled for the same quality and quantity of beer.

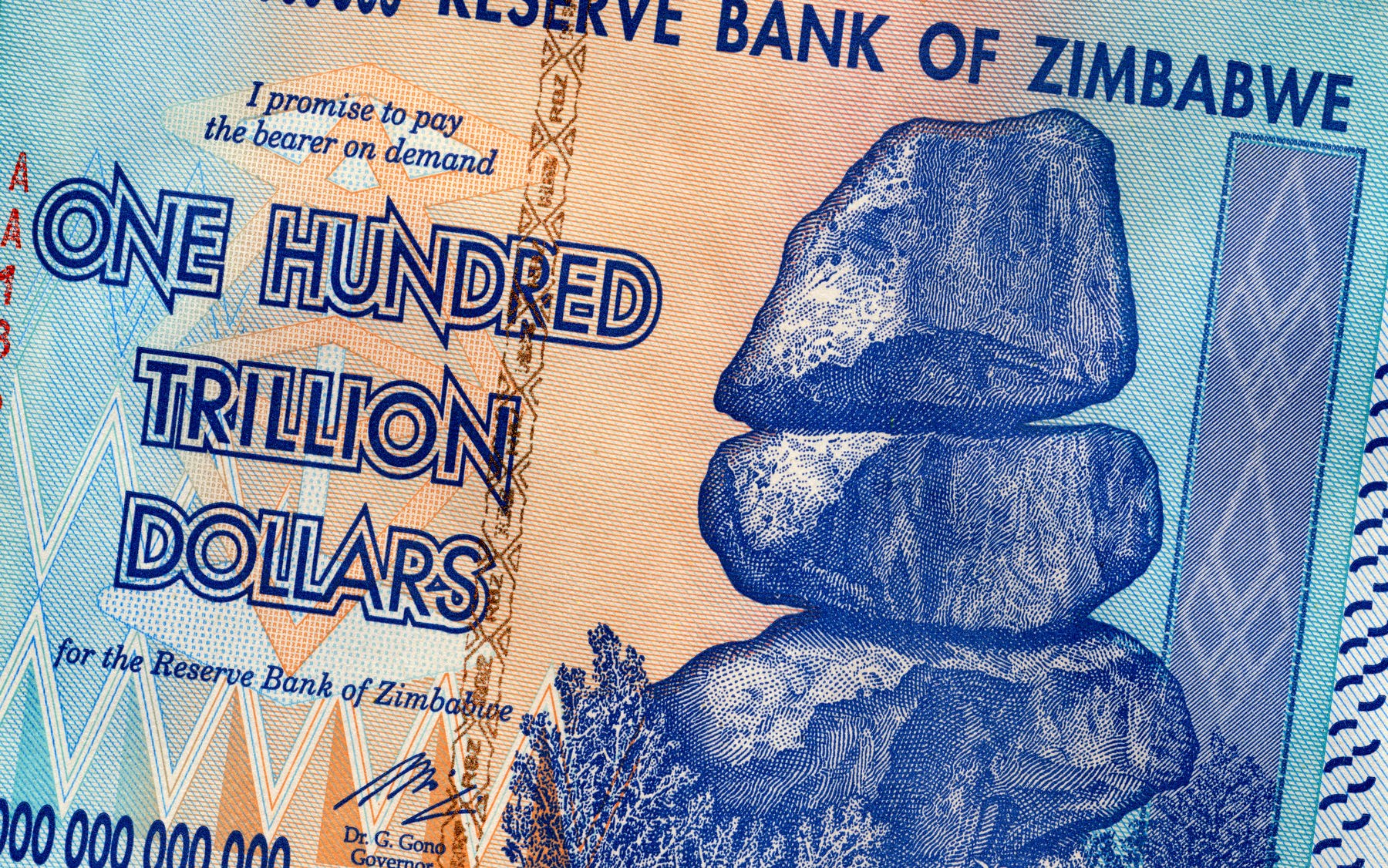

To put it in perspective, the most famous hyperinflations occurred in Zimbabwe and in Germany. In 2003, Zimbabwe’s monthly inflation rate hit 7.96 x 1010 percent, and in 1923 the German government’s hyperinflation caused the exchange rate to rocket to 4.2 trillion German Marks to one U.S. dollar.

Two Definitions of Inflation

Using the common definition, Bitcoin is deflationary because Bitcoin’s purchasing power increases over time.

However, the traditional definition of inflation, according to the British Currency School, was an increase in the supply of money that was unbacked by gold. According to Reinhart and Rogoff’s This Time is Different, governments have been inflating currency over the past 800 years.

Originally, governments would inflate the currency by debasing gold coins. During the 20th century, government inflation technology advanced to printing presses, and currently, governments are able to inflate the monetary base by digitally creating money by updating internal databases that track fiat money, which is predominately digital.

Using the traditional definition, Bitcoin is inflationary because the supply of Bitcoin increases over time.

Gold Is Inflationary, Too

Gold is considered the ultimate store of value because of one specific characteristic: scarcity. No person or group can will gold into existence. Instead, the supply is controlled by nature. Figure 1 (above) shows the supply of gold has had a stable inflation rate. The creators of Bitcoin designed its inflation rate to mimic gold’s stable inflation rate.

Figure 2 (below) shows the circulating Bitcoin since its creation in 2009. As the inflation rate decreases, the price for each Bitcoin should increase, ceteris paribus. Bitcoin’s inflation rate was hardcoded into the software that operates Bitcoin. Hardcoding Bitcoin’s inflation is similar to Milton Friedman’s K percent rule that called for an algorithmic and regulated inflation rate that would eliminate human-error and the temptation to manipulate the monetary base for political reasons. However, Bitcoin’s inflation algorithm was designed to make Bitcoin even scarcer than gold.

Good Stores of Value are Always Scarce

There is a fixed amount of 21 million Bitcoin that can be minted, which means that no coins can be minted once this amount is reached. Approximately 80 percent of the total amount of Bitcoin has already been minted. Bitcoin’s algorithmic inflation rate since 2010 is displayed in Figure 3 (below) and is explained in the original white paper written by Satoshi Nakamoto.

“To compensate for increasing hardware speed and varying interest in running nodes over time, the proof-of-work difficulty is determined by a moving average targeting an average number of blocks per hour,” Nakamoto explained. “If they are generated too fast, the difficulty increases”.

As of July, the inflation rate of Bitcoin was 4.25 percent. The difficulty re-adjustment makes it impossible to simply mine more Bitcoin by allocating more computer resources to the network. As more people try to mine Bitcoin, the software automatically increases the difficulty of successfully mining a Bitcoin and vice-a-versa.

Once the inflation rate reaches zero, miners will no longer be able to earn money from minting newly created bitcoins. Instead, transaction fees will have to increase or the number of transactions will have to increase. The last edition of the Crypto Research Report contains an in-depth explanation of how transactions are confirmed on the network and how miners earn income by confirming transactions and minting new coins.

Conclusion

Although Bitcoin and gold are currently inflationary monies, according to the traditional definition of inflation, their inflation rates are predictable and constantly decreasing. Similar to gold, Bitcoin’s annual inflation rate will eventually reach zero percent.

According to the mainstream economic definition of inflation, Bitcoin is deflationary because the purchasing power of Bitcoin increases over time. Currently, Bitcoin’s purchasing power is extremely volatile, although, this is expected to stabilize in the long-run. Since Bitcoin’s total supply is fixed, Bitcoin’s purchasing power will continue to grow slowly over time if demand continues to increase.