DeVos Confirmed: Everything They Said about Her Is False

Betsy DeVos has been confirmed as Secretary of Education, but just barely. In the course of the hearings, outrageous claims were made about her views. Most originated from the public school industry itself, which is clinging to old forms for dear life. The result has been nothing but confusion. Let’s look more carefully.

In an op-ed for the New York Times, U.S. Senator Maggie Hassan (D-NH) alleges that she is voting against Betsy DeVos for Secretary of Education because:

- DeVos opposes policies that allow “our young people, all of them, to participate in our democracy and compete on a fair footing in the workforce.”

- DeVos supports “voucher systems that divert taxpayer dollars to private, religious and for-profit schools without requirements for accountability.”

- “The voucher programs that Ms. DeVos advocates leave out students whose families cannot afford to pay the part of the tuition that the voucher does not cover; the programs also leave behind students with disabilities because the schools do not accommodate their complex needs.”

Each of those claims is belied by concrete facts, and Hassan is guilty of most of the charges she levels at DeVos. Also, Hassan sent her own daughter to a private school, an opportunity that she would deny to other children.

A Fair Footing

Under the current U.S. education system, the quality of students’ schooling is largely determined by their parents’ income. This is because wealthy parents can afford to send their children to private schools and live in neighborhoods with the best public schools. Such options narrow as income declines, and the children of poor families—who are often racial minorities—typically end up in the nation’s worst schools.

Contrary to popular perception, funding is not the primary cause of differences between schools. Since the early 1970s, school districts with large portions of minority students have spent about the same amount per student as districts with fewer minorities. This is shown by studies conducted by the left-leaning Urban Institute, the U.S. Department of Education, Ph.D. economist Derek Neal, and the conservative Heritage Foundation.

Moreover, contrary to the notion that certain minorities are intellectually inferior, empirical and anecdotal evidence suggests that with competent schooling, people of all races can excel. For example, in 2009, Public School 172 in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, New York, had:

- a mostly Hispanic population.

- one-third of the students not fluent in English and no bilingual classes.

- 80% of the students poor enough to qualify for free lunch.

- lower spending per student than the New York City average.

- the highest average math score of all fourth graders in New York City, with 99% of the students scoring “advanced.”

- the top-dozen English scores of all fourth graders in New York City, with 99% of students passing.

These and other such results indicate that school quality plays a major role in student performance. Hassan and other critics of school choice are keenly aware of this, as evidenced by the choices they make for their own children. For example, Obama’s first Education Secretary, Arne Duncan, stated that the primary reason he decided to live in Arlington, Virginia, was so his daughter could attend its public schools. In his words:

That was why we chose where we live, it was the determining factor. That was the most important thing to me. My family has given up so much so that I could have the opportunity to serve; I didn’t want to try to save the country’s children and our educational system and jeopardize my own children’s education.

Duncan’s statement is an admission that public schools in the D.C. area often jeopardize the education of children, but he would not let this happen to his child. Few parents have the choice that Duncan made because most cannot afford to live in places like Arlington, where the annual cash income of the median family is $144,843, the highest of all counties in the United States.

Other prominent opponents of private school choice—like Barack Obama, Joe Biden, and Bill Clinton—personally attended and also sent their own children to private K-12 schools. Likewise, Hassan’s daughter attended an elite private high school (Phillips Exeter Academy) where Hassan’s husband was the principal.

The existing U.S. education system does not provide an equal footing for children, but Hassan criticizes DeVos for supporting school choice, which would lessen this inequity. By its very definition, school choice allows parents to select the schools their children attend, an option that Hassan and other affluent people regularly exercise.

Taxpayer Money and Accountability

Four lines of evidence disprove Hassan’s claim that DeVos wants to “divert taxpayer dollars” to non-public schools “without requirements for accountability.”

First, private school choice generally increases public school spending per student, which is the primary measure of education funding. As explained by Stephen Cornman, a statistician with the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics, per-pupil spending is “the gold standard in school finance.”

Private school choice programs boost per-student funding in public schools because the public schools no longer educate the students who go to the private schools, which typically spend much less per student than public schools. This leaves additional funding for the students who remain in public schools.

According to the latest available data, the average spending per student in private K-12 schools during the 2011-12 school year was about $6,762. In the same year, the average spending per student in public schools was $13,398, or about twice as much. These figures exclude state administration spending, unfunded pension liabilities, and post-employment benefits like healthcare—all of which are common in public schools and rare in private ones.

Certain school costs like building maintenance are fixed in the short term, and thus, the savings of educating fewer students occurs in steps. This means that private school choice can temporarily decrease the funding per student in some public schools, but this is brief and slight because only 8% of public school spending is for operations and maintenance.

Second, school choice provides the most direct form of accountability, which is accountability to students and parents. With school choice, if parents are unhappy with any school, they have the ability to send their children to other schools. This means that every school is accountable to every parent.

Under the current public education system, schools are accountable to government officials, not students and parents. Again, Hassan knows this, because her son has severe disabilities, and Hassan used her influence as a lawyer to get her son’s public elementary school to “accommodate his needs.”

Unlike Hassan, people without a law degree, extra time on their hands, or ample financial resources are at the mercy of politicians and government employees. Short of legal action or changing an election outcome, most children and parents are stuck with their public schools, regardless of whether they are effective or safe. That is precisely the situation that DeVos would like to fix through school choice, but Hassan talks as if DeVos were trying to do the opposite.

Third, taxpayer funds are commonly used for private schools, and Hassan actually wants more of this. Her campaign website states that she “will fight to expand Pell Grants” but fails to reveal that these are often used for private colleges like, for example, Brown University, the Ivy League school that she, her husband, and her daughter attended (disclosure: so did this author).

In other words, Hassan supports using taxpayer money for top students to attend elite private universities, but she opposes the same opportunity for poor students to attend private K-12 schools.

Hassan’s position on college aid also undercuts her objection that DeVos supports programs that “leave out students whose families cannot afford to pay the part of the tuition that the voucher does not cover.” If that were truly Hassan’s objection, she would also oppose aid that doesn’t cover the full costs of every college, because that would leave out students who can’t pay the rest of the tuition.

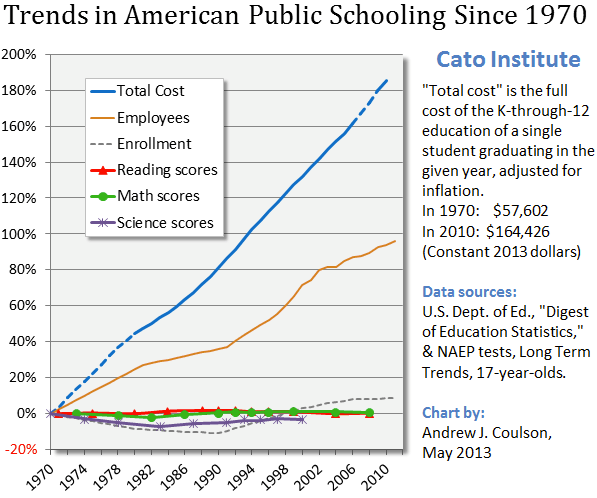

Fourth, contrary to Hassan’s rhetoric about accountability to taxpayers, she supports current spending levels in public K-12 schools, “debt-free public college for all,” and expanding “early childhood education” in spite of the facts that:

- the U.S. spends an average of 31% more per K-12 student than other developed nations, but 15-year olds in the U.S. rank 31st among 35 nations in math.

- federal, state, and local governments spend about $900 billion per year on formal education, but only 18% of U.S. residents aged 16 and older can correctly answer a word problem requiring the ability to search text, interpret it, and calculate using multiplication and division.

- the average spending per public school classroom is $286,000 per year, but only 26% of the high school students who take the ACT exam meet its college readiness benchmarks in all four subjects (English, reading, math, and science).

- federal, state and local governments spend $173 billion per year on higher education, but 80% of first-time, full-time students who enroll in a public community college do not receive a degree from the college within 150% of the normal time required to do so.

- 4-year public colleges spend an average of $40,033 per year for each full-time student, but one-third of students who graduate from 4-year colleges don’t improve their “critical thinking, analytical reasoning, problem-solving, and writing” skills by more than one percentage point over their entire college careers.

- the federal government funds dozens of preschool programs, and the largest —Head Start—spends an average of $8,772 per child per year, but it produces no measurable benefit by the time students reach 3rd grade.

In sum, Hassan supports pumping taxpayer money into programs with high costs and substandard outcomes, but she opposes doing the same for private K–12 schools that produce better outcomes with far less cost.

Left Behind?

Hassan’s claim that private school choice programs “leave behind students with disabilities because the schools do not accommodate their complex needs” is also false.

In Northern and Central New Jersey, there are more than 30 private special education schools that are approved by the state. As far as parents are concerned, these schools serve the needs of their children better than the public schools in their areas. If this were not the case, these private schools would not exist.

More importantly, if parents don’t think that a private school will be best for their special needs child, school choice allows them to keep the child in a public school that is better-funded thanks to the money saved by school choice.

In a recent brief to the Nevada Supreme Court, the nation’s largest teachers’ union, and its state affiliate argue that free-market voucher programs will lead to “cream-skimming—the drawing away of the most advantaged students to private schools––and lead to a highly stratified system of education.”

As detailed above, the current public school system is highly stratified by income, and income and education go hand in hand. Hence, the real issue is not stratification but what happens to students who stay in public schools. Contrary to the belief that school choice will harm these students, a mass of evidence shows the opposite.

At least 21 high-quality studies have been performed on the academic outcomes of students who remain in public schools that are subject to school choice programs. All but one found neutral-to-positive results, and none found negative results. This is consistent with the theory that school choice stimulates competition that induces public schools to improve.

Who Wins and Who Loses?

Wide-ranging facts prove that school choice is a win for students, parents, and taxpayers. However, it financially harms teachers unions by depriving them of dues, because private schools are less likely to have unions than public ones.

In turn, this financially harms Democratic politicians, political action committees, and related organizations, which have received about $200 million in reported donations from the two largest teachers’ unions since 1990. Unions also give many unreported donations to Democratic Party causes.

Teachers’ unions are firmly opposed to private school choice, and the National Education Association has sent an open letter to Democrats stating that “opposition to vouchers is a top priority for NEA.”

So why does Hassan oppose giving other children opportunities that she gave to her own children? Motives are difficult to divine, but the reasons she gave in her op-ed are at odds with verifiable facts and her own actions.

James D. Agresti is the president of Just Facts, a nonprofit institute dedicated to publishing verifiable facts about public policy.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.