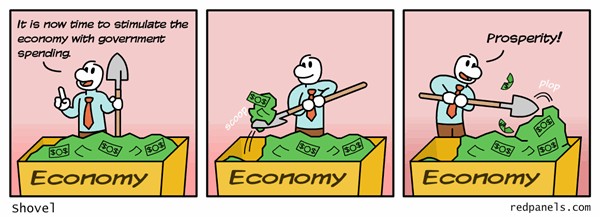

Keynesian economics is like Freddie Krueger, constantly reappearing after logical people assumed it was dead. The fact that various stimulus schemes inevitably fail should be the death knell for the theory, which is basically the “perpetual motion machine” of economics.

Indeed, I’ve wondered whether we’ve reached the point where the “debilitating drug” of Keynesianism has “jumped the shark.”

Yet Keynesian economics has “perplexing durability,” probably because the theory tells politicians that their vice of profligacy is actually a virtue.

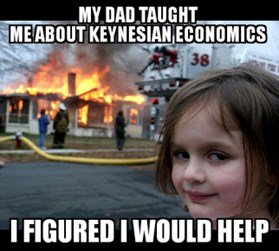

But there are some economists who genuinely seem to believe that government can artificially boost growth. They claim terrorist attacks and alien attacks can be good for growth if they lead to more spending. They even think natural disasters are good for the economy.

I’m not joking. As reported by CNBC, the President of the New York Federal Reserve actually thinks the economy is stimulated when wealth is destroyed.

Hurricanes Harvey and Irma actually will lead to increased economic activity over the long run, New York Fed President William Dudley said in an interview. …”The long-run effect of these disasters unfortunately is it actually lifts economic activity because you have to rebuild all the things that have been damaged by the storms.”

I’m always stunned when sentient adults make this kind of statement.

Should we invite ISIS into the country to blow up some bridges? Should we dynamite new buildings? Should we pray for an earthquake to destroy a big city? Should we have a war, featuring lots of spending and destruction?

All of those things, along with hurricanes and floods, are good for growth according to Keynesian theory.

Jeff Jacoby explains why this is poisonous economic analysis.

Could anything be more absurd? The shattering losses caused by hurricanes, earthquakes, forest fires, and other calamities are grievous misfortunes that obviously leave society poorer. Vast sums of money may be spent afterward to repair and rebuild, but society will still be poorer from the damage caused by the storm or other disaster. Every dollar spent on cleanup and reconstruction is a dollar that could have been spent to enlarge the nation’s reservoir of material assets. Instead, it has to be spent replacing what was lost. …No, hurricanes are not good for the economy. Neither are floods, earthquakes, or massacres. When windows are shattered, all of humanity is left materially worse off. There is no financial “glint of silver lining.” To claim otherwise is delusional.

By the way, I don’t think any Keynesians actually want disasters to happen.

They’re simply making a “silver lining” argument that a bad event will lead to more spending. In their world, what drives the economy is consumption, and it’s the role of government to either consume directly or to give money to people so they will spend it.

In a recent interview, I pointed out that investment and production are the real keys to growth (which is why I prefer GDI over GDP). Increased consumption, I explained, is a result of growth, not the cause of growth.

You’ll notice I also threw in a jab at the state and local tax deduction, a loophole that needs to be abolished as part of tax reform.

But let’s not get sidetracked.

For those who want to do some additional reading on Keynesian economics, I recommend this new study by a couple of professors. Here’s a blurb from the abstract.

…Keynesians assert that even wasteful government spending can be desirable because any spending is better than nothing. This simple Keynesian approach fails to account, however, for several significant sources of cost. In addition to the cost of waste inherent in government spending, financing that spending requires taxation, which entails an excess burden. Furthermore, the employment of even previously idle resources involves opportunity costs.

I’ll close by augmenting theory and academic analysis with some real-world observations.

Keynesian economics didn’t work for Hoover and Roosevelt, hasn’t worked for Japan, didn’t work for Obama, and didn’t work in Australia. Indeed, Keynesians can’t point to a single success story anywhere in the world at any point in history.

Though they always have an excuse. The government should have spent more, they tell us.

P.S. Since their lavish tax-free salaries are dependent on pleasing the governments that finance their budgets, international bureaucrats try to justify Keynesian economics. Here’s some recent economic alchemy from the IMF and OECD.

P.P.S. I frequently urge people to watch my video debunking Keynesian economics. Though I admit it’s not nearly as entertaining as the famous video showing the Keynes v. Hayek rap contest, followed by the equally enjoyable sequel, which features a boxing match between Keynes and Hayek. And even though it’s not the right time of year, here’s the satirical commercial for Keynesian Christmas carols.

Reprinted from International Liberty.

Daniel J. Mitchell is a Washington-based economist who specializes in fiscal policy, particularly tax reform, international tax competition, and the economic burden of government spending. He also serves on the editorial board of the Cayman Financial Review.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.