Reach Out and Access Someone

(This article is reprinted from the September 6, 1983, issue of ‘The Village

Voice’ and was written by Teresa Carpenter.)

Las Vegas in the rain is about as cheerful as Guam. So last November when the

storms that swamped Malibu swept inland to pound the roof and glass siding of

the Hacienda Hotel, I spent a lot of time curled up under the covers

contemplating the Future.

The Future seemed a pressing issue just then because I was nominally covering

COMDEX, a biannual convention where makers of computer hardware and software

unveil their new lines in an atmosphere of matter-of-fact futurism. The truth

of the matter was that I was a bewildered observer tagging along behind my

spouse equivalent, Steven, who writes a column for ‘Popular Computing’, belongs

to a little cadre of technology writers who cover these events with the espirit

of prospectors in a new gold rush.

One afternoon early in the convention week we went to lunch with another

technology writer from ‘Time’ magazine. The two were swapping industry gossip

when Steven stopped, turned to me, and said, not unkindly, “You can add

something if you like.” That made me so uncomfortable that I didn’t return to

the convention. I strode off as if I had some pressing business to conduct,

played the slots a while, and ended up back at my room burrowed under the

covers to contemplate my place in this new order.

The technological cleft that had been opening between Steven and me went back to

the previous year when we had both gotten Apples for word processing. Buying

the computers was originally my idea. Once we got them home, we both learned

word processing. I learned it faster. But I stopped there, while Steven’s

fascination with the technology impelled him to go further. He fussed with the

computer as if it were a beloved toy. He talked to people, read about

computers, wrote about them, and quietly became a lay expert.

My ignorance was most conspicuous in an area called “telecommunications” – that

is, using the computer to reach and talk to other people. It had not occurred

to me that I might ever want to do that until in perusing the small library in

Steven’s suitcase I came across ‘The Network Nation’, written by a pair of

social theoreticians named Starr Roxanne Hiltz and Murray Turoff. The book,

published in 1978, slightly preceded popular interest in computer technology and

didn’t receive much attention. Yet it contained a fascinating vision. In it

home computers are as common as the telephone. They link person to person,

shrinking, as the authors put it, “time and distance barriers among people, and

between people and information, to near zero.” In its simplest terms, ‘The

Network Nation’ is a place where thoughts are exchanged easily and

democratically, and intellect affords one more personal power than a pleasing

appearance does. Minorities and women compete on equal terms with white males,

and the elderly and handicapped are released from the confines of their

infirmities to skim the electronic terrain as swiftly as anyone else. What the

Network Nation promises is so sensible and humane that it leaves one embarrassed

to be living among contemporaries who take meetings.

��Hiltz and Turoff tended to speak of this society as if it were already a

reality. And it is true that over the past five years hundreds of networks have

spring up pocked by subcultures. There are massive governmental webs to

accommodate the needs of military analysts and artificial intelligence experts.

There are commercial networks like the Source and Compuserve, which sell canned

information and let users talk to one another. There are research and

development networks, which study the way users talk to one another. At the

most rudimentary level there are hundreds of electronic bulletin boards run by

amateur astronomers, gardeners, computer enthusiasts, and Marxists – anyone with

a home computer, one inexpensive piece of software, and a “modem.”

The modem, I knew, was critical to the enterprise. It dials up what is known as

a digital network to put your computer online, in contact with a “host”, a large

computer called a mainframe. As modems are fairly expensive, we got one Hayes

micromodem – a black box about five inches long – which we agreed to share.

From the beginning, however, it had been clear that Steven was Keeper of the

Fire. Having exhibited more initiative, he had laid claim to it. And during

the months after Las Vegas, as I expressed oblique curiosity in the modem, he

protected his prerogatives. He needed it for work.

I should explain that at any time I could have announced I needed the modem and

gotten it. But I didn’t. This passivity was less a result of the

inaccessibility of that black box than my suspicion of it. That I would have to

learn how it worked was inevitable, but to say “I’ll do it today” meant

admitting that some familiar things were on their way to oblivion. By midsummer

I was still at a standoff with the technology in my own home. The modem was not

going to make the first move. I decided that to deal with it, I would have to

whip up some artificial urgency – by writing about it. When I told Steven I

would be needing the modem for work, it sounded so reasonable that he just

shrugged and said, “Sure, call Art Kleiner in the morning.”

Art Kleiner is editor of ‘CoEvolution Quarterly’. More recently he was

recruited to help edit ‘The Whole Earth Software Catalog’, Stewart Brand’s

newest New Age venture. I had found him, on the couple of occasions we had met,

an uncommonly gentle apostle of the New Technology. Long before it was

fashionable, he wrote articles explaining networking to ordinary people. He

seemed a little more realistic than most of the gold rush writers, actually

admitting the possibility that all of this enthusiasm about telecommunications

might be hype.

He was, however, personally passionate about it. As a student at Berkeley in

the late ’70s, he had been mightily impressed by the work of Murray Turoff, who

was operating, under the auspices of the New Jersey Institute of Technology in

Newark, a network called the Electronic Information Exchange System. It was

known to its afficianados as EIES (pronounced “eyes”). Art went on a pilgrimage

to the East Coast to meet Turoff, who gave him a trial account on the system.

Art spent so much time there that he was made a “user consultant” charged with

guiding writers onto EIES.

When I called Art in San Francisco in the middle of July to tell him I wanted an

account on EIES, he uttered a beatific sigh. He would send an electronic

message, a sort of letter of introduction, to Turoff. There would be three or

four days’ wait until I received an account number and password. I would be

billed $75 a month plus connect time that runs between $3 and $8 an hour.

During that waiting period, I began to play around on other systems. Steven had

to make another trip to California, and this time left me not only the modem but

his password on Compuserve and a set of cursory instructions. One evening, I

settled in front of the terminal to make my first solo excursion into the

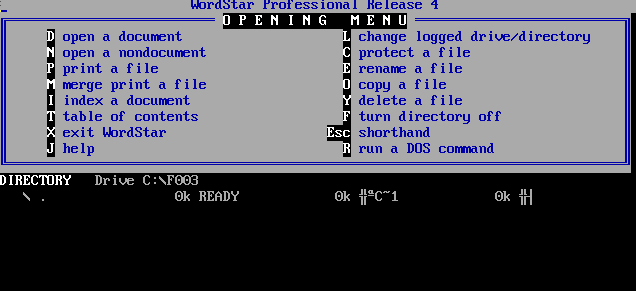

mystic. I took a floppy disk containing a piece of software called “Z-term,”

slid it into the slot of disk drive A, and closed the door. The computer hummed

and the screen suddenly came alive with glowing green letters. I typed “ZPRO”

to ready the modem to dial. Typed out the number of Telenet. Within the modem

a tiny red light began twinkling to dial the network.

The terrain at the border of Compuserve was more familiar to me than I expected.

I spotted, with relief, the “menu,” which displays a set of choices. I had used

it on earlier occasions when, after Steven had signed on, I would try to pull up

information. Never with very much success. The information services, for all

their taunted diversity, seemed to me cluttered with novelties like biorhythms

and airplane schedules. Steven professed to have run across one pocket of

esoterica which provided the floor plans of Czechoslovakian hospitals. The only

consistently useful data seems to exist for businessmen. Compuserve, which has

about 69,000 subscribers, recently conducted a user survey. More than 96 per

cent of those queried were men, 50 per cent of whom have household incomes of

more than $30,000 a year. This is a comparatively privileged world.

From the menu I selected “Home Services” and entered its number, “1,” after the

waiting prompt, an exclamation point that means the computer and its formidable

resources await your command.

Pressing the return button pulled up a more specific menu, which included news,

weather, sports and – “COMMUNICATIONS.” Entering its number at the prompt, I got

the communications menu, which included “electronic mail.” In this heavily

trafficked feature, users send what resemble teletyped messages to one another’s

electronic mail boxes. More intriguing, however, was option two, the “CB

SIMULATION.”

The simulator is, as the name suggests, a “citizen’s band” on which users across

America and Canada communicate in rapid one-liners fired in succession. The

CBers use handles – Loo Loo and Gandalf and Super Scooper. This sprawling

discourse is conducted with the abandon that anonymity affords. And late at

night these elfish identities convene to chat and play mind games. This

generally occurs on Channel 1 – reserved for “adult conversations.”

I signed on as “Sapphire.” The name had no particular significance, but it

apparently telegraphed something provocative for I was beggared by overtures.

One of these came from Lucky Lori. After the initial stir of a new persona on-

line had died down, she asked if I wanted to join her in private conversation by

entering the “/talk” mode. Lori, who I believe mistakenly took “Sapphire” to be

a variant of “Sappho,” was bisexual. After cordial preliminaries, during which

she confessed to being a little high, she asked if I had ever heard of

“Compusex.” I hadn’t. How is it different from an obscene phone call, I asked.

“More fantasy,” Lori said. But you’re missing sound, I noted. “Written word is

better,” she replied. I signed off on Lori but the following day fidgeted in the

full regret that follows any adventure one declines out of cowardice. A couple

of nights later I got on the board looking for Lori but was promptly hit on by

the Deadwood Kid, who lured me into the private mode. Deadwood was a

blue-collar worker (he said) and a sweet guy. When he asked if I knew about

Compusex, he was so unassuming, I asked him to go on.

Compusex did not unfold quite the same as an obscene phone call, although I

imagine it could have. Deadwood, it turned out, was a sensitive scenarist who

transported us to his living room in Northern California where we danced a while

to Barry Manilow before easing in step toward his bedroom.

It is worth noting that nothing, least of all a seduction, proceeds inexorably

in this medium. Although the CB operates in real time, there is always a couple

of seconds delay between responses, which meant that at one point while

ensconced in an imaginary bed we both claimed to be on top. The encounter was

furthermore plagued by technical interruptions, not the least of which was an

incoming telephone call which knocked me off-line.

The encounter was pretty arousing. Amazing when you consider that it was devoid

of sound, touch, and expression. This strange game illustrated how intimate the

expression of disembodied essences can be.

��

The elves who disport themselves on the channels have created an entire society

on-line. “CBland,” it is explained somewhere on the system, “is a town, a club,

a clique, a fantasy world, a dating service…or anything one wants it to be.”

What Compuserve and the Source apparently didn’t realize when they first put

together their potpourri of consumer goods is that people are not crying for

airline schedules and biorhythms or even stock quotations, but to talk to one

another. The one truly revolutionary thing that telecommunication offers is the

ability to transform time and space between human voices. The possibilities for

twisting the boundaries of conventional communication became clearer when I

finally got on to EIES.

It seemed eerily silent by contrast. Stepping through the menus of the

commercial services is like strolling anonymously through a Turkish bazaar.

Logging on to EIES, however, was like having crossed the threshold of a

monastery where monks, consecrated to the cause of research and development,

glide along the corridors out of reach of the novitiate.

There are about 1200 inhabitants in this little world. It is a neutral host to

groups of scientists, peace activists, executives, philosophers, and others.

Alvin Toffler and former FCC commissioner Nicholas Johnson are among the

notables who have tuned in from time to time to observe various scenarios of

future communication unfold under the ubiquitous guidance of Murray Turoff.

Turoff is known as “the father of computerized conferencing” for an idea that

grew out of work he did in the early ’70s for the Nixon administration. He was

an apolitical eccentric who, after receiving a doctorate in physics from

Brandeis University, had been recruited by a private think tank called the

Institute for Defense Analysis to design systems for playing war games by

computer. Turoff later went to a new operations research group of the Office of

Emergency Preparedness. In his free time there he designged an unauthorized

conferencing system. His superiors, when they discovered the experiment,

threatened to sue him for misuse of government property, but scaled down the

punishment to confiscating his terminal. Turoff regained his terminal and the

upper hand when the administration asked him to dust off his system to implement

the Wage-Price-Freeze Guidelines of 1971.

During the mid-’70s, when he was teaching computer science at the New Jersey

Institute of Technology in Newark, he received a grant from the National

Science Foundation to create an ideal system – one that offers three basic

“modes of interfacing,” or communicating.

��

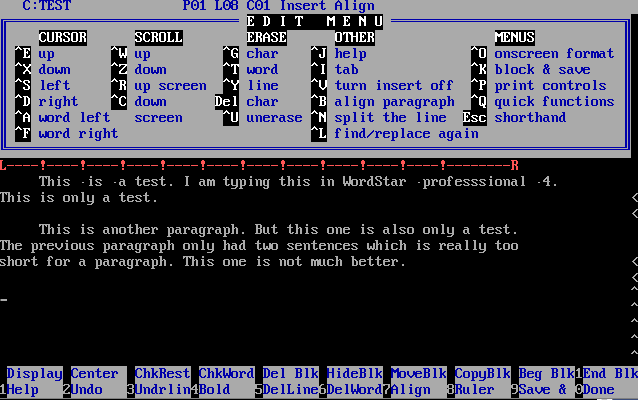

The simplest to imagine is “electronic mail.” It is like sending a teletype

message. After composing a message in a “scratchpad,” you assign it the user

number of the party to whom it is to be sent, then dispatch it with a keystroke.

The other two formats represent a more radical departure from the conventional

communications. “The notebook” is a workspace where people who are

geographically scattered can co-author or edit manuscripts. Further out on the

fringe is “the conference,” where people can convene and make decisions without

occupying the same space or even the same period of time.

I had learned about these things from ‘The Network Nation’; using them was quite

another matter. Though I had applied myself diligently to the users’ looseleaf

manual sent me by the EIES office in Newark, it was dense with lists of

commands. So arcane is this system, I learned, that *nobody* knows all of the

commands on EIES. I surmised that rather than proceeding logically, I would be

better off just slopping around on the system and working backward from my

mistakes to some guiding principles.

In fumbling about the keyboard trying to compose a plea to Art for help, I

accidentally – and quite inexplicably – opened a conference with myself as

moderator. Sort of like ‘WarGames.’ *More* disturbing was that my wailing

missive – “I am running into brick walls. Cannot seem to contact another human

intelligence” – was posted prominently there as the first entry. This left me

anxious thereafter that my messages might misfire, landing in the box of a

meditating monk.

A few days later, when I was composing in note, another novitiate crash-landed a

one-liner into my scratchpad, “I’m just getting used to this thing! Where are

you?”

Struggling to respond, I discovered the command “???”. I replied, “Lost in

space and time.”

His name was Lee Rhodes and he was production manager for personal computers at

Hewlett-Packard’s plant in Silicon Valley. He was in charge, he said, of

converting the plant to Japanese manufacturing and was on-line to discuss it

with other executives. It was comforting to discover that Lee, who had actually

designed computers, was also having trouble getting the hang of things. But he

was adventuresome and asked if I had used the “link” command. The “link,” as it

suggests, allows two people to converse in one-line thoughts. It is slow going

on EIES – about a 10- to 30-second lag between entries – but is very popular

among new users. The monks, I am told, sniff at newcomers who use a lot of

links. First of all, crashing in on someone’s screen with a link could disturb

their work. More important, however, it represents a shallow attachment to

real-time communication. The sincere telecommunicator will be weaned within a

couple of weeks from dependence upon real time and begin to explore other modes,

where conversation takes place “asynchronously.”

Over the next three weeks, Lee and I moved to a notebook, an abstract domain

that took on the properties of a physical location. We were rarely on-line at

the same time. Whenever he was on, he would post an entry; whenever I was on, I

would post a reply. I learned from this asynchronous exchange that he was

entertaining guests from Europe, had two cats, and had been divorced for four

years. Although he claimed to be maladroit as a writer, he was remarkably

skillful at compensating for the lack of visual and verbal cues. On the CB I

had noticed the elves have developed a clumsy shorthand for the missing cues,

typing “(Blush)” or “(Grin)”. These became annoying because they gave the

exhange the quality of comic book dialogue. Lee, however, was careful to

articulate what pleased or had offended him, the essence of good on-line

etiquette.

The notebook had an unusual effect on time. The conversation took place over

days and weeks, acquiring a longer rhythm than face-to-face encounters. An

entry conveyed more ideas than a spoken utterance. It resembled letter-writing

in this way. But the colloquy was more urgent and continuous than a conventional

correspondence. This asynchronous rhythm becomes even stranger when more than

two people are involved, as they are in the scores of conferences being

conducted at any time on EIES.

��My earlier impression of silence was dispelled once I got within earshot of the

monks clustered and conferring in the alcoves. Some of these gatherings were

public and welcomed anyone. There was the EIES Poetry Corner, where users could

sign in and leave an opus generally signed with a pen name. There were the EIES

News Service and a spot for film critique called the Critics Corner. It was

moderated by a 13-year-old boy who shared an account with his father, a

commodities trader.

Art invited me into two of his own conferences, one for eliciting reviews for

‘The Whole Earth Software Catalog.’ I posted a critique of a program written by

a California proctologist for reading Tarot. The other was a private conference

for magazine writers where the discussion always seemed to return to writing

about technology.

Art once remarked to me, “Studying EIES is like listening to the users of the

first telephone talk about the telephone.” Conversations are often

self-conscious, probably because users are aware of being part of an

experiment. On the one hand the novelty spawns an unnatural enthusiasm. In

trying to overcome the coldness of the medium, some personalities appear manic.

On the other hand the prospect of shooting a message into the void is so awesome

that it can inhibit spontaneity.

I was nervous at first about the prospect of having my own fumbling observed by

some unseen presence. This fear of being watched is fairly common, according to

Turoff and Hiltz. They call it the “fishbowl effect.” For that reason they

tell a new user, as a matter of policy, the types of information that are being

kept for research purposes. Since EIES exists for the purpose of studying the

communication that goes on within its veins, the inner group counts for each

user, the total number of sign-ons, messages sent, and conferences “accessed.”

They do not, they say, keep records of those to whom the messages are sent or

what conferences are accessed. There is a running transcript of virtually all

of one’s exchanges kept within the host computer. You must simply trust that it

will not be read by the programmers.

Beyond anxiety about privacy, the pioneers chatting on EIES are also often

puzzled by the strangeness of the new medium. Conferencing, particularly,

requires a new way of thinking. Its languorous rhythm means that you can not

come on the system at any point and command the entire scope of events. Turoff

and Hiltz have likened this limitation to looking through a peephole into a

giant ballroom: vision is circumscribed by the aperture. One way of surveying

the terrain is to read all the conference entries from beginning to end, but

these sometimes run into hundreds. The better moderators will write summaries

of the proceedings at intervals. A newcomer reading the entries sequentially

may also become frustrated trying to find a line of discussion. Ideas do not

build in a linear fashion. Since no one has to speak in turn, conferees may sign

on and add a reply to a comment that was entered two weeks and ten comments

earlier. That lots of little conversations are going on within the bigger one

means you must learn to read them stereoptically.

��

The fact that it is never anyone’s “turn” to speak creates a sort of populist

chaos. This is, on the one hand, very democratic. “Typical face-to-face

meetings,” explains Elaine Kerr, a sociologist who is head of the EIES user

consultants, “are dominated by men, by people who speak the loudest, by people

with the highest hierarchical positions. But the computer meeting gives women,

and minorities, [those] who are not appropriate to the culture, the opportunity

to voice their opinion.”

EIES recently conducted an experiment where it set 24 groups on-line to work on

a problem – what items does one need to survive in the Arctic? “Right” answers

were provided by Mounties and Eskimos. The EIES groups with more women did

better than those dominated numerically by men. “Now why were they better

decisions, we really don’t know,” says Roxanne Hiltz. “Maybe more of the women

were Girl Scouts.” What the study revealed, however, is that conferencing

leaves women and minorities freer to voice their opinions, and the more

information that gets out, the quantifiably better the decisions to follow.

The potential for telecommunications to blast away social barriers and to get

information circulating among minorities and women has been explored on a small

scale by groups like Community Memory, a group of Berkeley leftists who during

the early ’70s placed terminals in public places. That experiment languished

when the equipment kept breaking down. They are trying to get it going again

and there are presently several pilot projects underway to promote the peace

movement, but these are hampered by the fact that not all of the people who need

to belong on that network have computers.

What was also apparent to me from reading the entries in a couple of social

justice conferences on-line is that they tend to generate rhetoric that meanders

aimlessly in this fluid environment. Those who seem able to direct computer

conferencing most effectively are those who go in for strong leadership. This

is the province of industrialists, about 200 of whom I found on EIES. There are

executives of major American corporations who have been on-line since April to

make recommendations to the White House Conference on Productivity to be held in

Washington in September. One of them, a Xerox vice-president named Paul

Strassmann, was reputed to conduct a mean conference. He agreed to let me look

in as long as I agreed not to publish any of the content. (I had been assured

privately that the transcripts of those discussions, which dealt with measuring

the productivity of information workers, contained no secrets that might topple

the Republic.)

Strassmann, whom I imagined to resemble Jason Robards, did not allow his

conference to turn into, as he described it, “one grand electronic bull

session.” His conferees, who all went through a training session in Houston,

were asked to add only “issues” or “recommendations.” If someone came up with a

particularly good idea, he or she would be appointed an “Issues Manager” charged

with whipping that idea up into a recommendation. Strassmann himself processed

and edited those ideas into “Gutenbergian form,” a xeroxed report that will be

presented to the White House Conference.

When I asked the moderator if he found conferencing satisfactory, he replied:

“I was able to take your message, disassemble it electronically into the Q&A

format and get it back to you in about 20 minutes. In contents, format and

substance it surely beats anything else we could have done.”

��I messaged Paul – on-line one tends to use first names or nicknames, which

creates an illusory intimacy – to tell him that while, yes, we had handled our

interview with dispatch, I sort of missed the old face-to-face approach where a

reporter could seize upon an interesting point and probe. I had already

learned how hard it was to lob hardballs on-line from a little experiment I was

conducting on the side.

I had decided to conduct interviews in my own misconceived conference. I

invited Art Kleiner, then Roxanne Hiltz, Elaine Kerr, Murray Turoff, and others

to answer questions. There were 11 queries dealing with privacy and the quality

of life on-line. Since asking them one by one and waiting for responses could

have taken weeks, I posted them all at once. As a result my sources fluttered

in graciously, like tropical fish nibbling at this or that question, ignoring

the unpleasant ones. After about ten days, my conference was dead. I was not

as quipped as a captain of industry for the rigors of moderating. There are just

some things you have to ask in person.

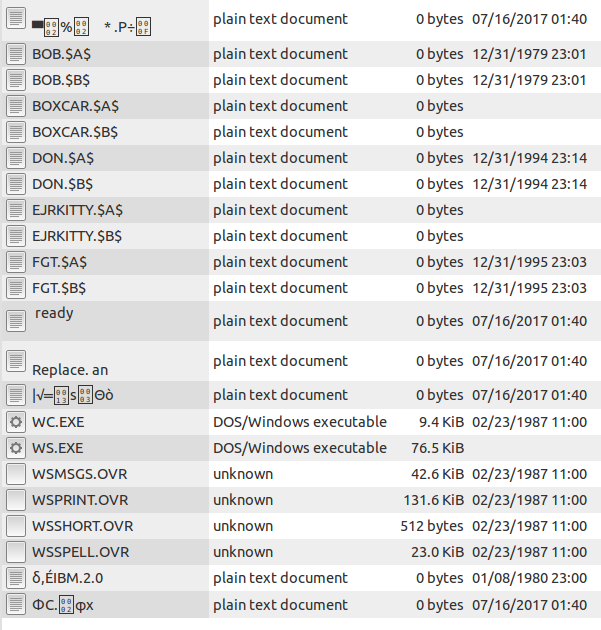

Art Kleiner offered me his guest quarters, a living room in his San Francisco

apartment. The room, nearly empty except for a pile of quilts and a cot, is a

spartan outpost of the Network Nation. Art is not much into creature comforts.

In one corner of the room, however, was a workspace handsomely appointed with a

KayPro computer, which serves as a nexus of his tasks on EIES and ‘The Whole

Earth Software Catalog.’

Having been separated from my own computer during a three-day business trip

across country, I knew I would have messages waiting. And seeing the KayPro, I

felt an instant urge to log on. Art mused that this was the behavior of a

“communications junkie,” one who comes to depend upon the thrill of finding

response on-line. Art said he knew all about that.

“I was the perfect addict,” he said referring to a period in 1979 when, briefly

out of work, he first found EIES. “I had lots of free time. I was breaking up

with the woman I cared most about. I logged in to escape…and EIES was the

only place that really accepted me at that time.”

Art came to think of EIES, he explained, as a “dreamworld,” where one with

intellect and an antic nature could command a following. “People liked reading

what I wrote,” he said. In person Art has the studied demeanor of an ascetic.

On-line, however, I had found him a much more flamboyant character, zinging

messages full of energy and wry abuse. That pleased him. “Writing well on EIES

is like being good looking. This system is for writers. It’s like being

captain of the football team.”

��

Art’s virtuosity sails at full tilt in a conference called the Soap Opera. This

is where the monks of EIES, including the eminent Murray Turoff, go to play. In

a make-believe village called Disbelief they spin an ongoing yarn, trying on

personae like costumes. Steven, I learned, has been cavorting since January as

“Scoop Frothmouth,” ace reporter for the ‘Disbelief Bugle.’ Art has played as

many as 20 characters of both genders at one time, but appears most frequently

as Starving Artist. Starv has for three years been carrying on a fantasy affair

with a beautiful and willful vamp named Wistful. Her anima is Elaine Kerr, the

on-line sociologist who began consulting for EIES from Columbus, Ohio.

“I got to know Elaine pretty early on,” Art explains. “She is charismatic

on-line. Very dynamic. A petulant and intense character. And very

self-indulgent, which I always find charming in women.”

Art and Elaine have never met, although each sought out the other’s published

picture. Last spring Starv took Wistful on a mythical trip to the Caribbean

where he made love to her in the sand. It was a strange gesture born of events

in the real world. “I was overworked and almost desperate at the time,” Elaine

explains. “So he wrote it in for me. Roxanne understood my delight and the

true nature of this gift, which I can’t begin to convey in a message.”

Elaine recently moved to New Jersey to be physically closer to EIES. When I

returned from California, I sent Murray an electronic message suggesting that

he, Roxanne, Elaine, Scoop, and I all go to dinner. They suggested a French

restaurant in Westfield. Steven confessed to me sometime before we caught the

train that Scoop had once tried to seduce Wistful. This little revelation was

made with impunity since I, having cuckolded him on Compuserve, was in no

position to reproach.

Elaine Kerr was a short dark woman. She was quiet at first, aware perhaps that

we all were familiar with the exploits of the vamp Wistful. But she became

warmer, ebullient in fact, as dinner and two bottles of wine brought everyone’s

fibrillated personae into alignment. Roxanne, who wore an embroidered Victorian

shawl and a gladiola blossom tucked into her dark hair, talked rapidly and

intelligently, sometimes affectionately mocking Murray Turoff, the visionary.

“Murray Turoff says,” she says, “when you build a computer system, you’re

building a social system. Your own social world. It operates the way you like

social worlds to work. And he loves building these social worlds and making

them…watching them work.”

Turoff the Visionary, who sits beside her, is an affable, bearish man wearing a

plaid coat. He had endured himself to me with a message sent some days

earlier. “I am by nature a slow reflective thinker…” he wrote. “Therefore I

assume in face-to-face groups an air of contemplative wisdom to disguise my slow

wit. On-line, of course, I have no such problem since instant response is not

required. You might say I created this medium to satisfy my own needs.”

“She’s not kidding,” Murray intones to the gathering around the table. “…I’m

designing a human social system.”

“You could design a dictatorship as well,” interjects Elaine.

��”I’d love to do it,” Murray muses in the abstract. “All I need is the right

company. Some companies operate under a feudal system. If I was doing a

dictatorship, first of all, you couldn’t send a message> to anyone unless I

first approved the message. Okay? If we had voting, I’d get 10 votes to your

one. And I would have access to your files. Now you can imagine that I could

see that to some managers.”

“We presented this to one very large corporation,” Roxanne continues. “The

Dictator Design, tongue in cheek. And they said, ‘That sounds wonderful. We’ll

take it.’ And on the other hand, when I gave them the results of [the

experiments] which showed them that this medium freed women to make equal

contributions, they said, ‘We don’t want that.'”

I was incredulous. “Sure,” Murray replied. To Murray the construction of

worlds is an intriguing game. He regards the alternatives with dispassionate

curiosity. Roxanne is the social conscience of the two. Unlike Murray, she

believes that the behavior of people determines the design of social systems.

The Network Nation, he explains, should not be a sprawling, comprehensive,

homogenous system. Rather, it should be a collection of hundreds or thousands

of smaller systems, “intentional communities” for purposes as varied as

political debate and a big game of bridge. Keep things small so they can be

controlled by the groups that operate them. People should be able to design the

way they want to live and also stand guard over their own data bases.

“I think we both believe,” she says, “that the most desirable communities for

telecommunications are like electronic small towns. They number in the

thousands, not in the tens of thousands. What happens on something like EIES

with only 1200 people total is that everyone can know someone or know of someone

who knows them. There are only three programmers. Those three could get [into

files] but they have ties with a lot of users. The community ties are such that

[there are] social pressures to treat each other with dignity. It works.”

What if the CIA came around asking for a private message?

“There will be a fire,” says Roxanne resolutely. “There will be a fire.”

When the first bottle of wine came, I proposed a toast to the Network Nation.

That was a presumptuous thing to do. I really didn’t have the credentials, but

on the tide of such heady debate, one feels expansive. One feels exclusive. One

certainly feels relieved not to be caught without a modem on the cusp of a new

age. In the end, it could all come to nothing, but who wants to be left on the

outside?

“To the Network Nation,” I said and everyone clinked glasses. “May it grow,

prosper, and remain democratic,” Roxanne replied.