The coronavirus is back in force. Many nations around the world are seeing alarming rises in cases and deaths, totals that in many instances exceed the highs reached in March, April, and May.

From the beginning of the pandemic, governments around the world have tried to tame the virus. All have failed, to varying degrees.

Whether governments implement draconian lockdowns, modest lockdowns, or no lockdowns at all, the virus has spread. Some countries with harsh lockdowns have fared better; many have fared worse. As some have pointed out, the virus doesn’t seem to care what policies you put in place.

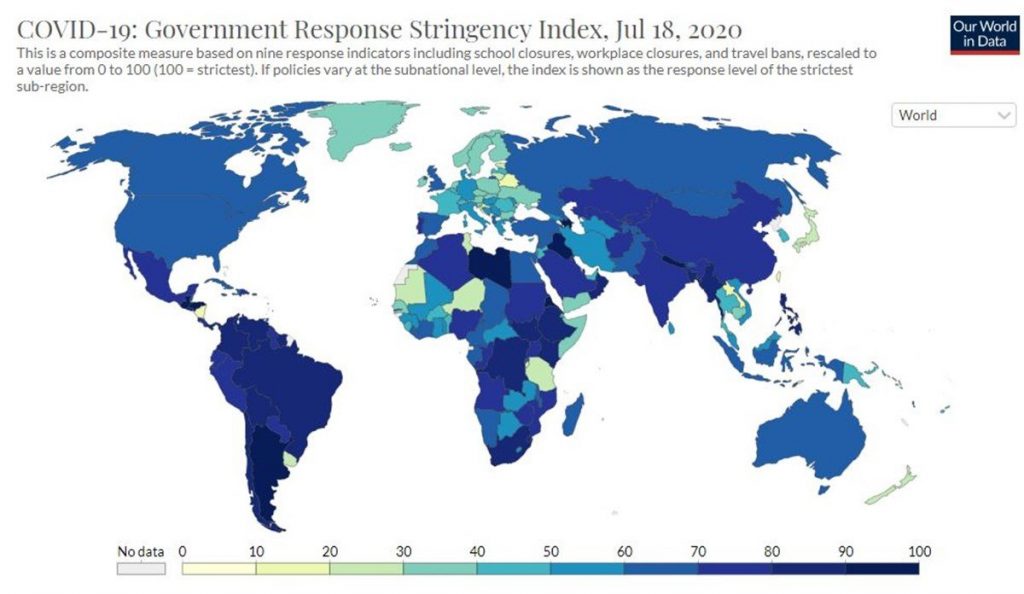

Belgium, for example, has the second highest COVID-19 death rate in the world even though it implemented one of the strictest lockdowns in the world (81.5 stringency). Italy and Spain had even harsher lockdowns, and both countries are also among the most devastated by the virus. (Italy’s current death rate is lower than that of Belgium and Spain, but the country is facing a resurgence of the virus that looks positively frightening.)

We can measure lockdown stringency because of a feature created by Our World in Data, a research team based at the University of Oxford that produces information in all sorts of wonderful charts and graphs.

While most of the world went into lockdown in March, Swedish officials chose to forgo a full lockdown, opting instead for a “lighter touch” approach that relied on cooperation with citizens, who were given public health information and encouraged to behave responsibly.

Our World in Data shows Sweden’s government response stringency never reached 50, peaking at about 46 from late April to early June. (As a point of reference, the US averaged a stringency of about 70 from March to September.) This is well below the top stringency of Spain (85) and Italy (94).

Yet, Sweden’s per capita death rate is lower than Spain, Belgium, Italy and other nations despite the fact that it did not initiate a lockdown. As a result, Sweden’s economy was spared much of the damage these nations suffered (though not all).

Despite the apparent success of Sweden’s strategy, the Swedes have found themselves attacked. The New York Times has described Sweden’s policy as a “cautionary tale,” while other media outlets have used it as an illustration of how not to handle the coronavirus.

Critics of Sweden’s policy point out that although Sweden has experienced fewer deaths than many European nations, it has suffered more than its Nordic neighbors, Finland and Norway.

This is true, but it needs to be contextualized.

Norway and Finland have some of the lowest COVID-19 death rates in the world, with 54 deaths per one million citizens and 66 per million respectively. This is well below the median in Europe (240 per million) and Sweden’s rate (605 per million).

What these critics fail to realize is that both Finland and Norway have had less restrictive policies than Sweden for the bulk of the pandemic—not more lockdowns.

Norway’s lockdown stringency has been less than 40 since early June, and fell all the way to 28.7 in September and October. Finland’s lockdown stringency followed a similar pattern, floating around the mid to low 30s for most of the second half of the year, before creeping back up to 41 around Halloween.

When people compare Sweden unfavorably to Finland and Norway to dismiss its laissez-faire policy, they are drawing the opposite conclusion from what the data point really reveals. Yes, Finland and Norway have lower deaths than Sweden—but they have actually been more laissez-faire than their neighbor for the majority of the pandemic.

Since June, Finland and Norway have had less restrictive government policies than Sweden, and both nations have endured the coronavirus remarkably well. They have been among the freest nations in the world since early June, and COVID-19 deaths have been miniscule.

Neither country even has a mask mandate, though both implemented mask recommendations in August. In Norway, private gatherings in public places are still permitted, though the capacity was recently reduced to 50 people (down from 200).

In Finland, people say daily life hasn’t changed very much.

“My daily life actually hasn’t been affected too much,” healthcare assistant Gegi Aydin told one local news station.

The lighter touch approach can be seen in their economies, as well. In the second quarter of 2020, Norway and Finland saw their economies contract by 6.3 percent and 6.4 percent respectively. That’s about half the 11.8 percent drop of the European Union, and well below that experienced by Spain (-18.5%) and the United Kingdom (-19.1%). It’s even lower than that of Sweden, which saw a decline of 8.6 percent.

Despite their low lockdown stringency, Norway and Finland are among the only places in Europe you’ll find considered safe for travel.

As I’ve pointed out before, people aren’t attacking the results of Sweden’s policies. They are attacking the nature of its policies. Of course, there are many nations that have been hit much harder than Sweden. But these nations are ignored because they don’t threaten the narrative that government lockdowns work, and that millions more would have died without them.

Norway and Finland show that the coronavirus doesn’t care about government policy. Their numbers have remained low with moderately strict lockdowns and with laissez-faire policies.

With the coronavirus resurging around the world, there is talk of implementing another round of crippling lockdowns. World leaders are facing immense pressure to “do something.”

This would be a mistake. Lockdowns come with severe and deadly unintended consequences. Moreover, they have proven utterly ineffective at taming the virus—which is why the World Health Organization is now advising against their use.

The reality is, humans are unwilling to accept how powerless they are to stop this virus. They are unwilling to admit they cannot control it.

Decades ago, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, the economist F.A. Hayek warned of the dangers of such hubris. If man continued to live in ignorance of the limits of his knowledge, it would breed a “fatal striving to control society – a striving which makes him not only a tyrant over his fellows, but which may well make him the destroyer of a civilization…”

It’s a lesson that has never been more important. We’ll soon know if it’s one we’re finally prepared to learn.

Jon Miltimore

Jonathan Miltimore is the Managing Editor of FEE.org. His writing/reporting has been the subject of articles in TIME magazine, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, Forbes, Fox News, and the Star Tribune.

Bylines: Newsweek, The Washington Times, MSN.com, The Washington Examiner, The Daily Caller, The Federalist, the Epoch Times.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.