Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg wants more government regulation of social media. In a March 30 op-ed for The Washington Post, Zuckerberg trots out the innocent-sounding pablum we’ve come to expect from him:

I believe we need a more active role for governments and regulators. By updating the rules for the Internet, we can preserve what’s best about it — the freedom for people to express themselves and for entrepreneurs to build new things — while also protecting society from broader harms.

But what sort of regulation will this be? Specifically, Zuckerberg concludes “we need new regulation in four areas: harmful content, election integrity, privacy and data portability.”

He wants more countries to adopt versions of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation.

Zuckerberg Wants Government Regulation

Needless to say, anyone hearing such words from Zuckerberg should immediately assume this newfound support for regulation is calculated to help Facebook financially. After all, this is a man who lied repeatedly to his customers (and Congress) about who can access users’ personal data, and how it will be used. He’s a man who once referred to Facebook users as “Dumb F-cks.” Facebook lied to customers (not to be confused with the users) about the success of Facebook’s video platform. The idea that Zuckerberg now voluntarily wants to sacrifice some of his own power and money for humanitarian purposes is, at best, highly doubtful. (Although politicians like Mark Warner seem to take it at face value.)

Fortunately for Zuckerberg, thanks to the economic realities of government regulation, he can both support government regulation and enrich himself personally.

Those who are familiar with the effects of government regulation will not be surprised to hear a billionaire CEO throw his support behind it. Large firms with dominant market share have long made peace with government regulation because it often helps these firms create and solidify monopoly power for themselves.

Specifically, there are three ways that regulation will help Facebook.

One: Regulations Will Give Facebook More Monopoly Power

Many Facebook critics like to claim that Facebook is a natural monopoly. That is, they think Facebook is so dominant in the marketplace, that it can use its supposed market power to keep out competitors. We’re told that Facebook has so many users, no serious competition will ever be possible.

But remember MySpace? People used to say exactly the same thing about that social media platform. A recently as 2007, The Guardian was asking “Will Myspace ever lose its monopoly?” Xerox corporation was once a tech powerhouse, as well. It has now all but disappeared.

Obviously, the answer to The Guardian‘s question is “yes.” But we’re now hearing about how Facebook is a monopoly. The reality, however, is that unless governments artificially erect barriers to entry, no firm can expect a safe place as a dominant firm. Other firms with new ideas will come along, threatening the older firm’s dominance.

The answer to this problem, from the point of view of a firm like Facebook, is to make things more expensive and difficult for smaller startups and potential competitors.

Facebook knows that if government regulations of tech firms increase, the cost of doing business will increase. Larger firms will be able to deal with these additional costs more easily than smaller startups. Big firms can access financing more easily. They have more equity. They already have a sizable market share and can afford to be more conservative. Large firms can absorb high labor costs, higher legal costs, and other high fixed costs brought on by regulation. A high-regulation environment is an anti-startup, anti-entrepreneurial environment.

Two: Zuckerberg and Facebook Will Help Write the New Rules

In an earlier age, many might have taken Zuckerberg’s new proclamation as sincere. Fortunately, we live in a cynical age, and even a beat reporter at Mashable knows how this game is played. Mashable‘s Karissa Bell writes:

It may seem obvious that Zuckerberg’s proposal is self-interested, but it’s important to remember that his ideas are, of course, designed to help Facebook….

And by touting the social network’s existing work around political advertising and content moderation, Facebook has an opportunity to determine the rules the rest of the industry will also have to abide by.

Part of the reason Zuckerberg has made peace with the idea of government regulation is the knowledge that Facebook will be one of the most powerful groups at the negotiating table when it comes to writing the new regulations. In other words, Facebook will be in a position to make sure the new rules favor Facebook over its competitors.

This is a common occurrence in regulatory schemes and is known as “regulatory capture.” When new regulatory bodies are created to regulate firms like Facebook, the institutions with the most at stake in a regulatory agency’s decisions end up controlling the agencies themselves. We see this all the time in the revolving door between legislators, regulators, and lobbyists. And you can also be sure that once this happens, the industry will close itself off to new innovative firms seeking to enter the marketplace. The regulatory agencies will ensure the health of the status quo providers at the cost of new entrepreneurs and new competitors.

Moreover, as economist Douglass North noted, regulatory regimes do not improve efficiency, but serve the interests of those with political power:

Institutions are not necessarily or even usually created to be socially efficient; rather they, or at least the formal rules, are created to serve the interests of those with the bargaining power to create new rules.

After all, how much incentive does the average person have in monitoring new regulations, staying in touch with regulators, and attempting to affect the regulatory process? The incentive is almost zero. The incentive for regulated firms, on the other hand, is quite large.

Not only will a small start-up lack the resources and political pull to challenge Facebook in the rule-making sphere, but those small firms won’t be large enough to be considered important “stakeholders” on any level. Thus, Facebook will continue to wield more power than its smaller competitors through its regulatory power.

Three: It Will Limit Facebook’s Legal Exposure

Another big benefit of regulation for Facebook will be the potential for using government regulation to limit Facebook’s legal liability when things go wrong. Bell continues:

By offloading decisions about harmful content, privacy rules, and elections onto third-parties, Facebook may not have to take as much of the heat when mistakes are made.

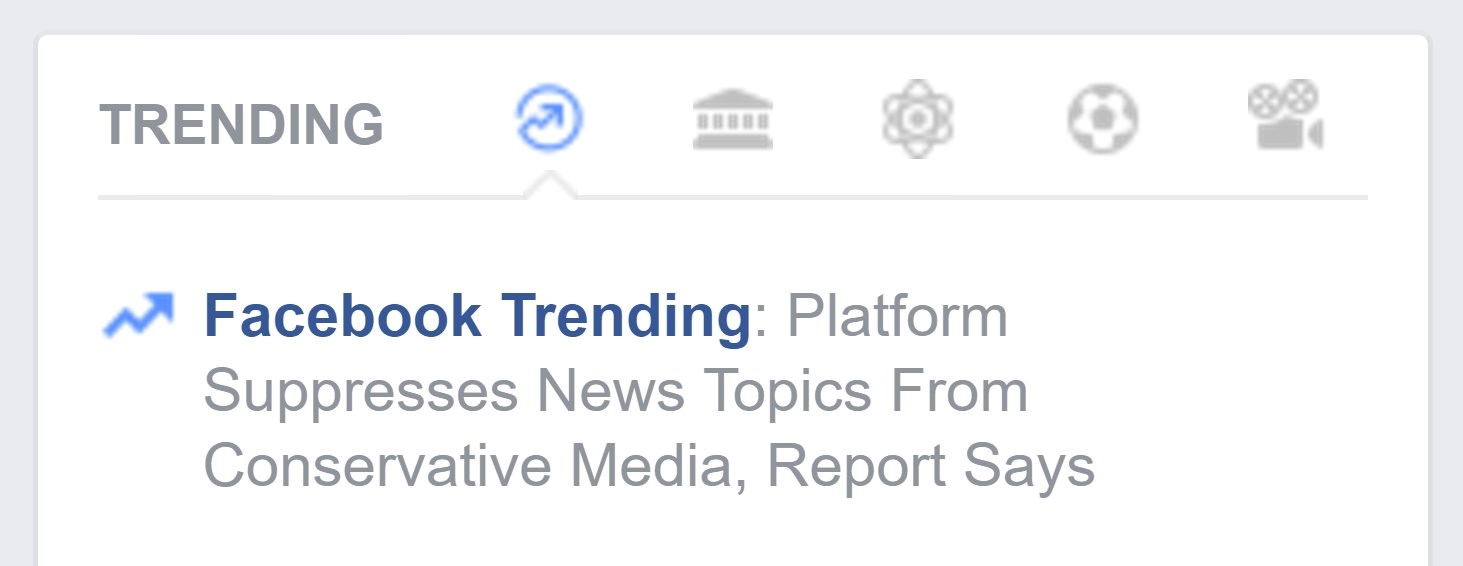

Put another way, Facebook can protect itself from both the legal and public-relations repercussions to itself when it uses its platform to delete the posts and visibility of users with whom Facebook employees disagree.

As FTC commissioner Brendan Carr put it, Facebook’s proposed regulatory agenda would allow it to “outsourc[e] censorship.” Not only would this put the federal government in a position to be directly determining which opinions and ideas ought to be eliminated from tech platforms, it would also allow Facebook to pretend to be an innocent third party: “Don’t blame us for deleting your posts,” Facebook could then say. “The government made us do it!”

Moreover, regulation can be employed by firms like Facebook to shield the firm from lawsuits. Potentially, in the marketplace, Facebook could be sued for using its platform to endanger domestic abuse victims or victims of suicide. Whether or not the firm should be found guilty of such things would be complex legal questions decided on a case-by-case basis. However, regulation can be used to circumvent this process entirely, and serve the interests of large, abusive firms.

This phenomenon was explained by Murray Rothbard in the context of construction regulations:

Suppose, for example, that A builds a building, sells it to B,and it promptly collapses. A should be liable for injuring B’s person and property and the liability should be proven in court, which can then enforce the proper measures of restitution and punishment. But if the legislature has imposed building codes and inspections in the name of “safety,” innocent builders (that is, those whose buildings have not collapsed) are subjected to unnecessary and often costly rules, with no necessity by government to prove crime or damage.

They have committed no tort or crime, but are subject to rules, often only distantly related to safety, in advance by tyrannical governmental bodies. Yet, a builder who meets administrative inspection and safety codes and then has a building of his collapse, is often let off the hook by the courts. After all, has he not obeyed all the safety rules of the government, and hasn’t he thereby received the advance imprimatur of the authorities?

Let’s apply this to the tech industry: Firm A is a new startup which has developed a way to make money in a way that satisfies consumers and does not expose them to any unwanted harassment, de-platforming, or violations of privacy. Meanwhile, Facebook (Firm B) continues to use its dominance in the regulatory process to keep in place costly regulations that prevent new startups from making much headway. These same regulations, however, continue to allow privacy violations, and other abuses up to a certain threshold established by regulators.

Thus, the outcome is this: Firm A is unable to deploy its new, inventive, non-abusive model at all because regulatory costs are too high. Meanwhile, Facebook can continue to endanger and abuse some users because regulations allow it. Moreover, Facebook enjoys greater immunity from lawsuits because it complies with regulations. Thus consumers are denied both the benefits of the new startup and legal remedies from suing Facebook for its continued abuse.

In short, Zuckerberg’s pro-regulation position is just a pro-Zuckerberg position. By further politicizing and regulating the internet, policymakers will assist large firms—and their billionaire owners—in crushing the competition, and ensuring the public has fewer choices.

This article is republished with permission from the Mises Institute.

Ryan McMaken

Ryan McMaken is the editor of Mises Wire and The Austrian. Ryan has degrees in economics and political science from the University of Colorado and was the economist for the Colorado Division of Housing from 2009 to 2014. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.