It is graduation time again, and students are getting ready to leave college and enter the workforce. Let’s imagine some such student named Johnny. Johnny’s parents have a graduation surprise for him. They have decided to pick up all of the remaining payments on his car. What a fantastic graduation gift! Johnny is ecstatic, and everyone is happy.

A month or two later, Johnny is living at home but has a job. It isn’t great, but it is a start. One day, his mom mentions that the car is dirty and needs to be washed. Hmm. Johnny agrees but essentially blows it off. A week goes by, and Johnny’s dad asks when the last oil change was and suggests that it probably needs one.

Another week or two goes by, and the veil drops. Johnny’s parents tell him that “since we are paying for the car, you had better take care of it.” It’s at this point that Johnny realizes that what his parents offered him at graduation was not a gift at all. They were entering into a contract.

There is a difference between a gift and a contract. A gift allows the receiver of the gift to do whatever he wants with the gift. If Johnny wanted to put the car in a demolition derby, then it would be totally up to him. No one else would have any say. A gift leaves the receiver free and clear of any commitments. A contract, on the other hand, is quite different. A contract places an obligation on each side of the agreement. Some contracts can be rather strict and onerous. Others, like Johnny’s contract, can be rather light.

At first Johnny’s contract was, “We (the parents) will make the car payments, and you (Johnny) enjoy using the car.” The unstated clause in the contract was that since the parents were making the payments, they had an ownership stake in the car. Over time, this ownership stake in the car could extend to washing it, changing the oil, and maintaining the car in good working order.

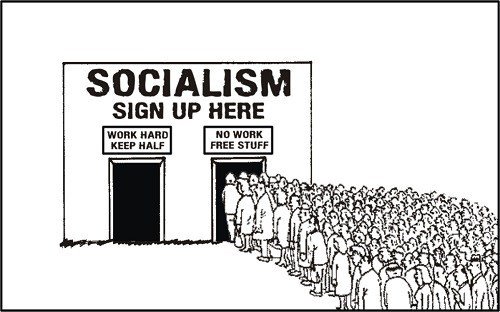

As we look around the world, we see that Western Civilization is making the same bargain, albeit in less obvious ways. I want to highlight two of them—Universal health care and Universal Minimum Income (sometimes called a Universal Basic Income).

The Dual Tragedies of Charlie Gard and Alfie Evans

In the UK, two cases have grabbed the international headlines that concern the state killing two babies—Charlie Gard and Alfie Evans. These young children (Charlie died at 11 months, 24 days, and Alfie’s second birthday would have been May 9, 2018) were taken to the hospital because something was wrong. The state attempted to cure them but eventually gave up and decided to pull the plug.

The parents sued the National Health Service system. The courts sided against the parents, saying that they did not own their child. The State had a superior claim. These rulings were made despite the facts that: (1) Italy made Alfie an Italian citizen, (2) the Vatican issued passports, (3) the Pope had transportation on standby, and (4) they—Italy and the Vatican—would have taken over the responsibilities for the children’s treatment.

Money was raised and, thus, they would no longer be a financial burden to the British health care system. None of these arguments mattered. The court not only ruled that life support was to be withdrawn, but food and water were also denied.

By accepting universal health care, the British people have not accepted a gift but a contract. Under a universal health care system, you do not own yourself; you are a ward of the State. There is a contract. Some might even call it a social contract. By accepting universal health care, you accept the contract. The State has said that it would start picking up all of the remaining car payments for you except it isn’t car payments, it’s health care payments. As a result, the state now has a superior claim on your health care than even you, yourself, do.

Universal Minimum Income Is Less Overt but No Less Sinister

It was recently announced that Finland’s experiment with a universal minimum income will come to an end by the end of the year. Undaunted by Finland’s reversal, Stockton, California, has decided to give it a try themselves. Many people support the idea of a universal minimum income.

Of course, we expect many on the Left and those in Silicon Valley to support it—people like Elon Musk. The Left supports it because it is a step towards a more egalitarian society. The Silicon Valley techies support it because many think that as Artificial Intelligence replaces the jobs of regular workers, unemployment will skyrocket. These unemployed people will have little chance to work and will need some mechanism to survive. Thus, the idea of a universal minimum income is growing.

Surprisingly, there are a good number of libertarians who are also in favor of it—people like Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, and Charles Murray. There are several efficiency arguments that make economic sense, but these efficiency arguments miss the deeper picture. A universal minimum income is not a gift where the receiver is in the free-and-clear of any commitment, where the recipient can do whatever he wants with the gift.

Like universal health care, the universal minimum income is a contract. The details of this contract are not really relevant because at the heart of this contract is the implicit recognition that the state owns the recipient. In the same way the parents are making a claim on the car because they are paying for it, the state is paying for you and, thus, they own you.

Who Owns You?

There is a danger in these universal programs. They might be economically efficient. (I doubt it, but let’s assume that it is true.) The deeper point is that under these contracts you are giving up your sovereignty. Do you own yourself? Or does the State own you? We need to recognize the difference between a gift and a contract. These government programs are never gifts; they all come with strings attached. These strings bind and imprison. And so, will Johnny get to live his own life or become a marionette? Even Pinocchio realized the merits of cutting the strings and being a real boy.

What the state offers might be a nice prison, but it doesn’t alter the underlying reality that you cannot escape. It reminds me of the British series The Prisoner where the main character has been sent to “The Village.” They have given him an apartment, food, clothing, and medical care—basically, all that he could want—and in exchange, they simply want information. When we will stand and claim, as the main character does, that “I will not make any deals with you. I’ve resigned. I will not be pushed, filed, stamped, indexed, briefed, debriefed, or numbered. My life is my own. I resign.”

In a world of universal health care and universal minimum income, you cannot resign. Please enjoy life in The Village. “Be seeing you.”

Dr. Paul F. Cwik is a Professor of Economics and Finance at the University of Mount Olive; and since 2013, he has taught the BB&T classes on Free Enterprise at North Carolina State University.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.